Alain Touwaide

and

Emanuela Appetiti

Solanaceae in Antiquity

Botany, Pharmacotherapeutics, Pharmacy

A Preliminary Study

Several taxa of the family identified since Linnaeus as Solanaceae can be recognized in the ancient Greek botanical and medical literature. The family is complex and is still studied to fully understand its phylogenesis. This complexity is reflected in the ancient Greek texts, without confusions, however. Based on textual and iconographic documentation, this study focuses on botanical description and representations with ensuing identification according to contemporary taxonomy, as well as on therapeutic indications and pharmaceutical preparations. It is based on the two major oeuvres on medicinal plants and pharmacotherapeutics of classical antiquity, De materia medica by Dioscorides (1st cent. A.D.) and treatises by Galen (129-after [?] 216 A.D.). This Preliminary Study aims make the ancient botanico-therapeutic literature available and accessible beyond the circles of classical scholarship. It is textually comprehensive, philologically accurate, and scientifically specific, and opens the way for an extensive analysis of the genus in Antiquity

List of illustrations

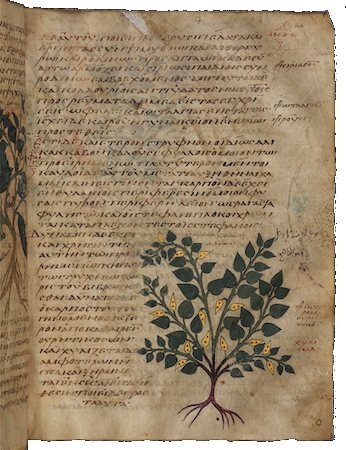

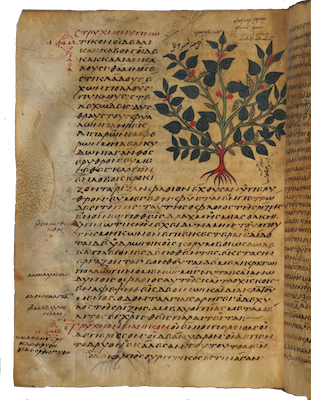

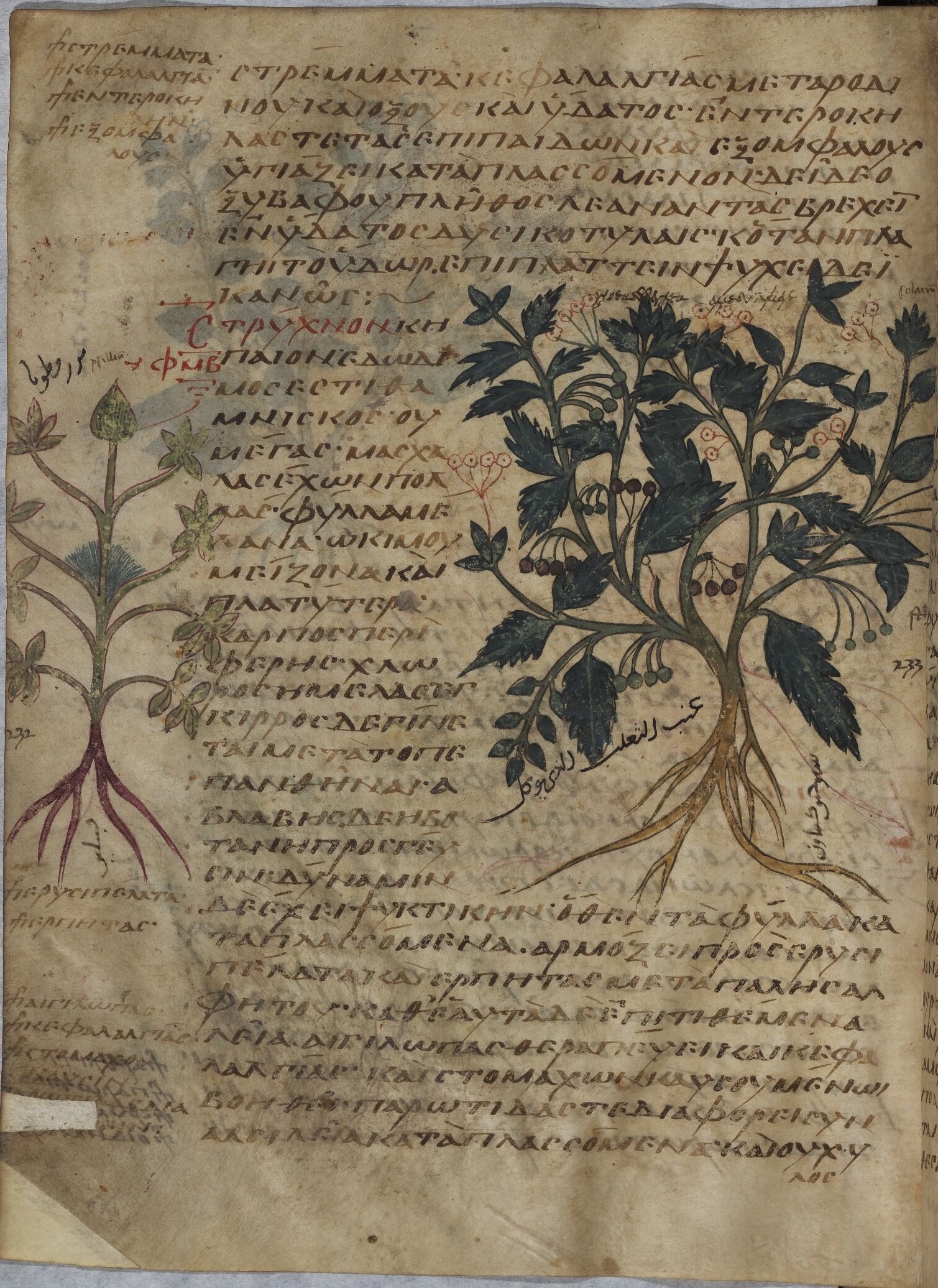

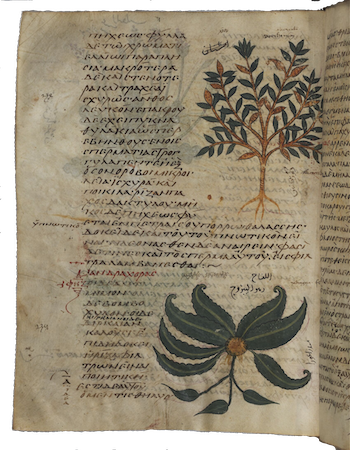

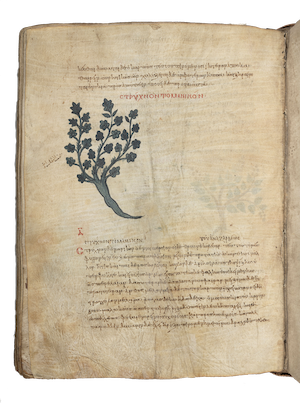

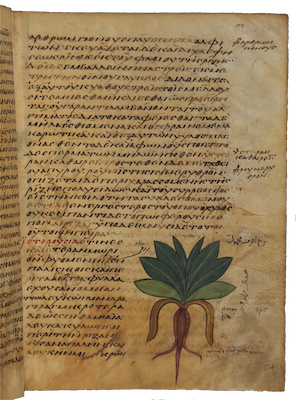

1. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 102r

(στρύχνον-ἁλικάκκαβον-struchnon alikakkabon)

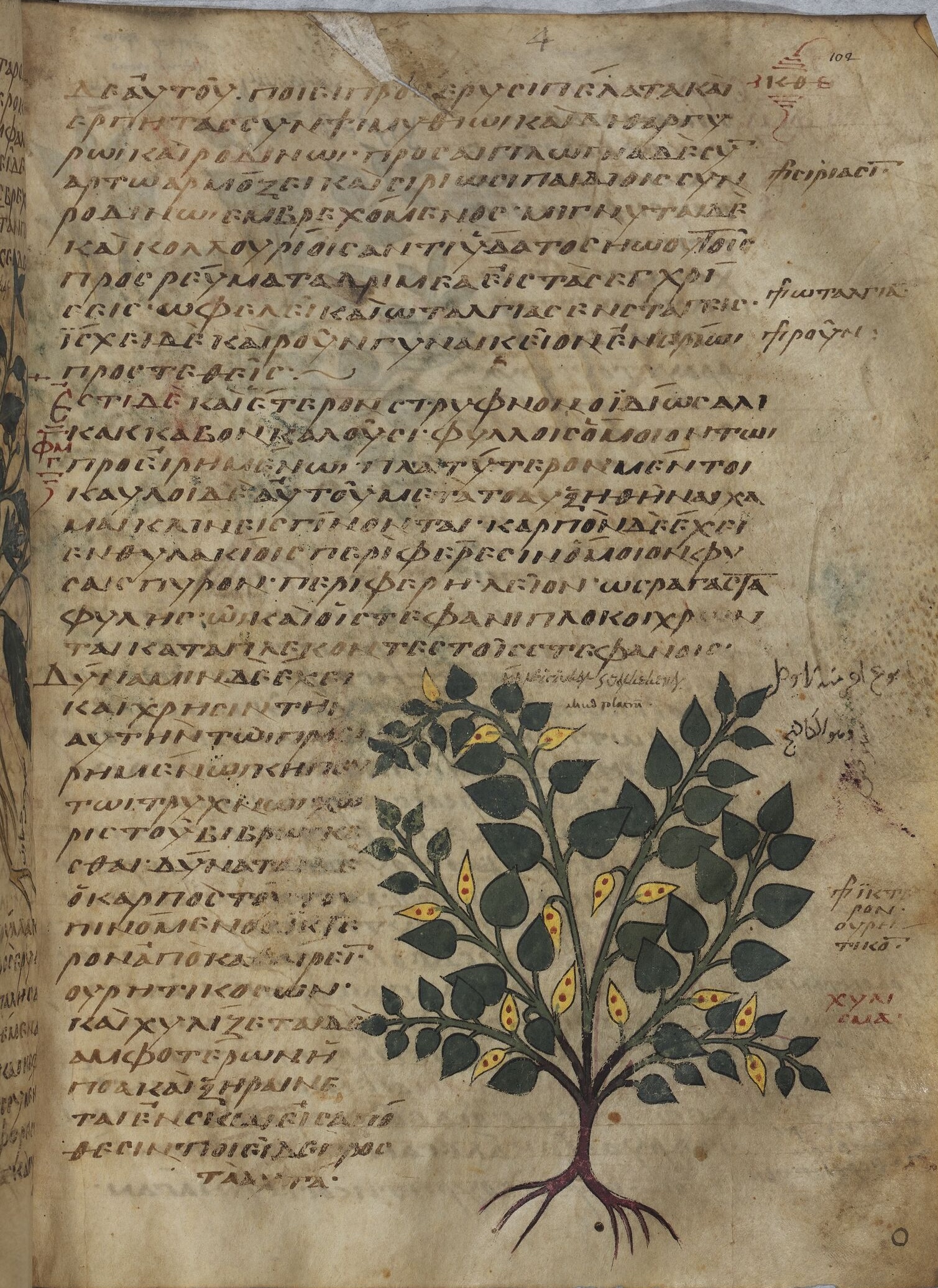

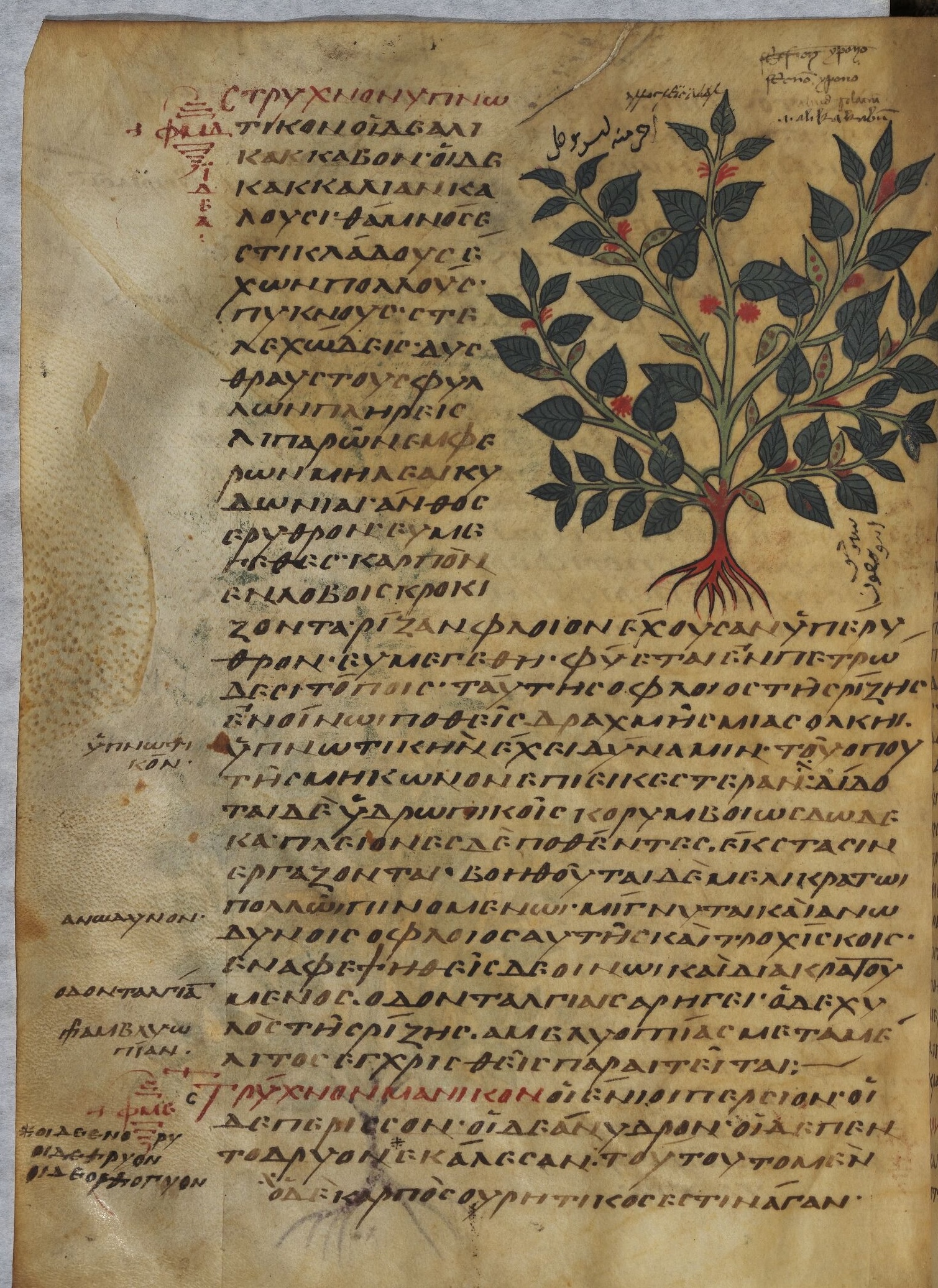

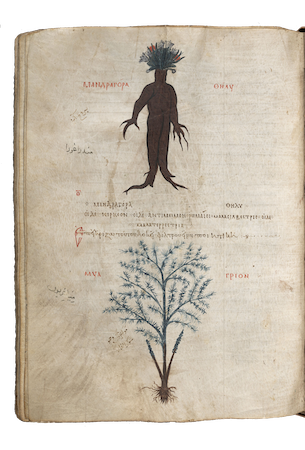

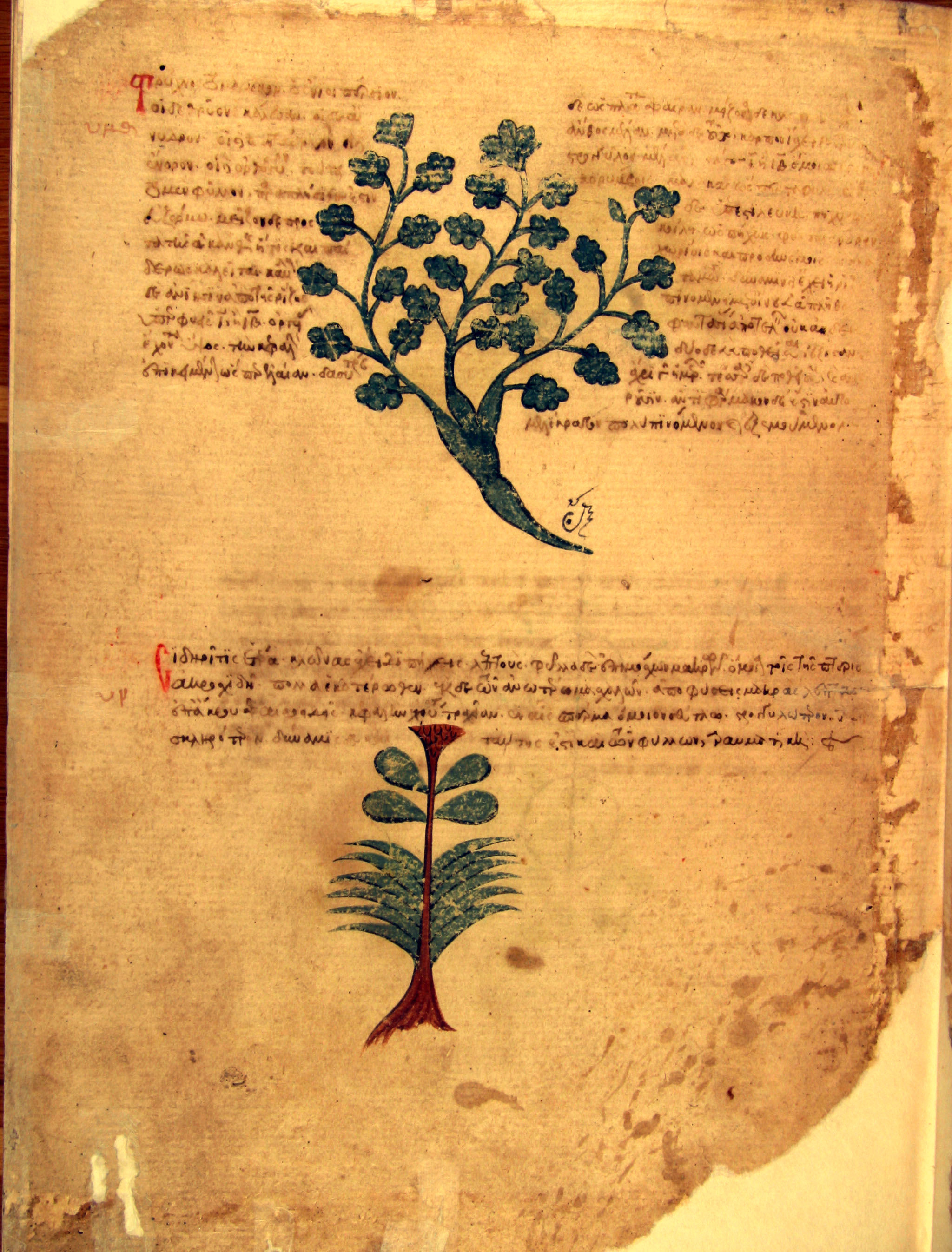

2. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 104r

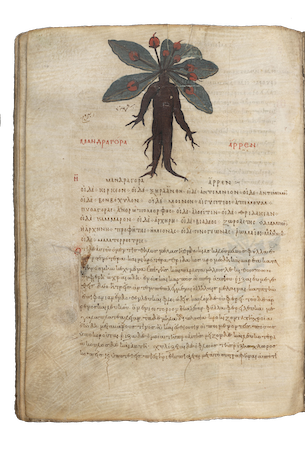

(μανδραγόρα ἄρρεν-mandragora arren)

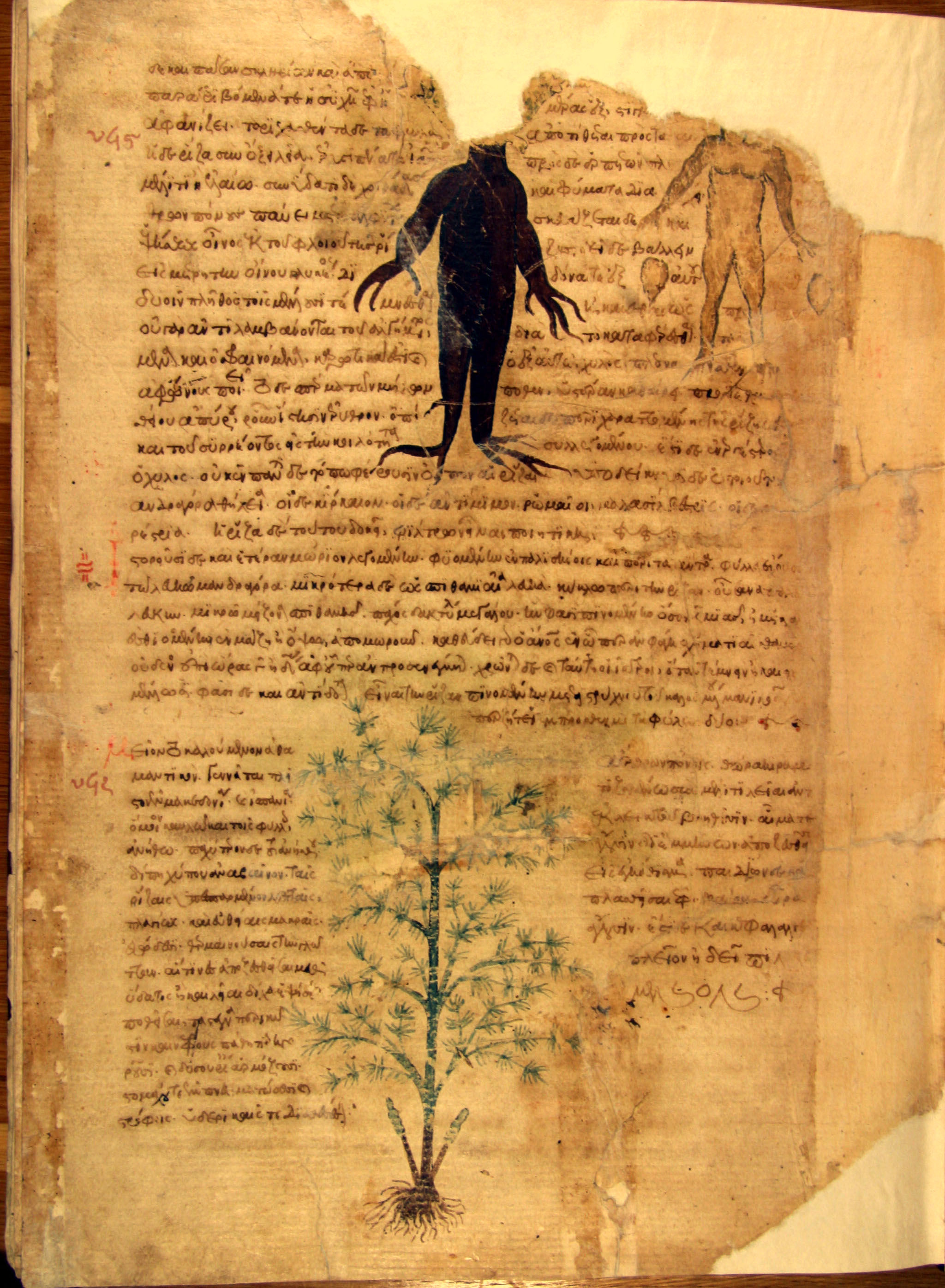

3. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 101v

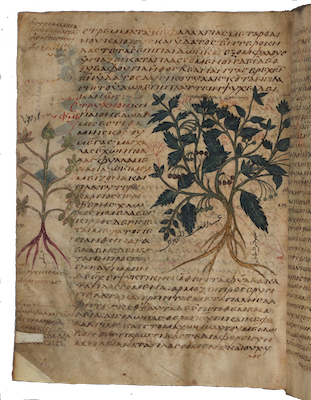

(στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion)

4. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 102v

(στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon)

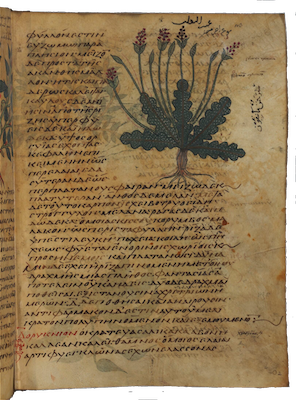

5. Naples, National Library, Ex Vindobonensis graecus 1, f. 148r

(φυσαλλείς-fusallis)

6. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 102r

(στρύχνον-ἁλικάκκαβον-struchnon alikakkabon)

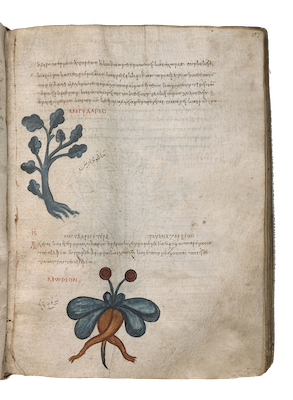

7. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M 652, f. 146r

(στρύχνον-ἁλικάκκαβον-struchnon alikakkabon)

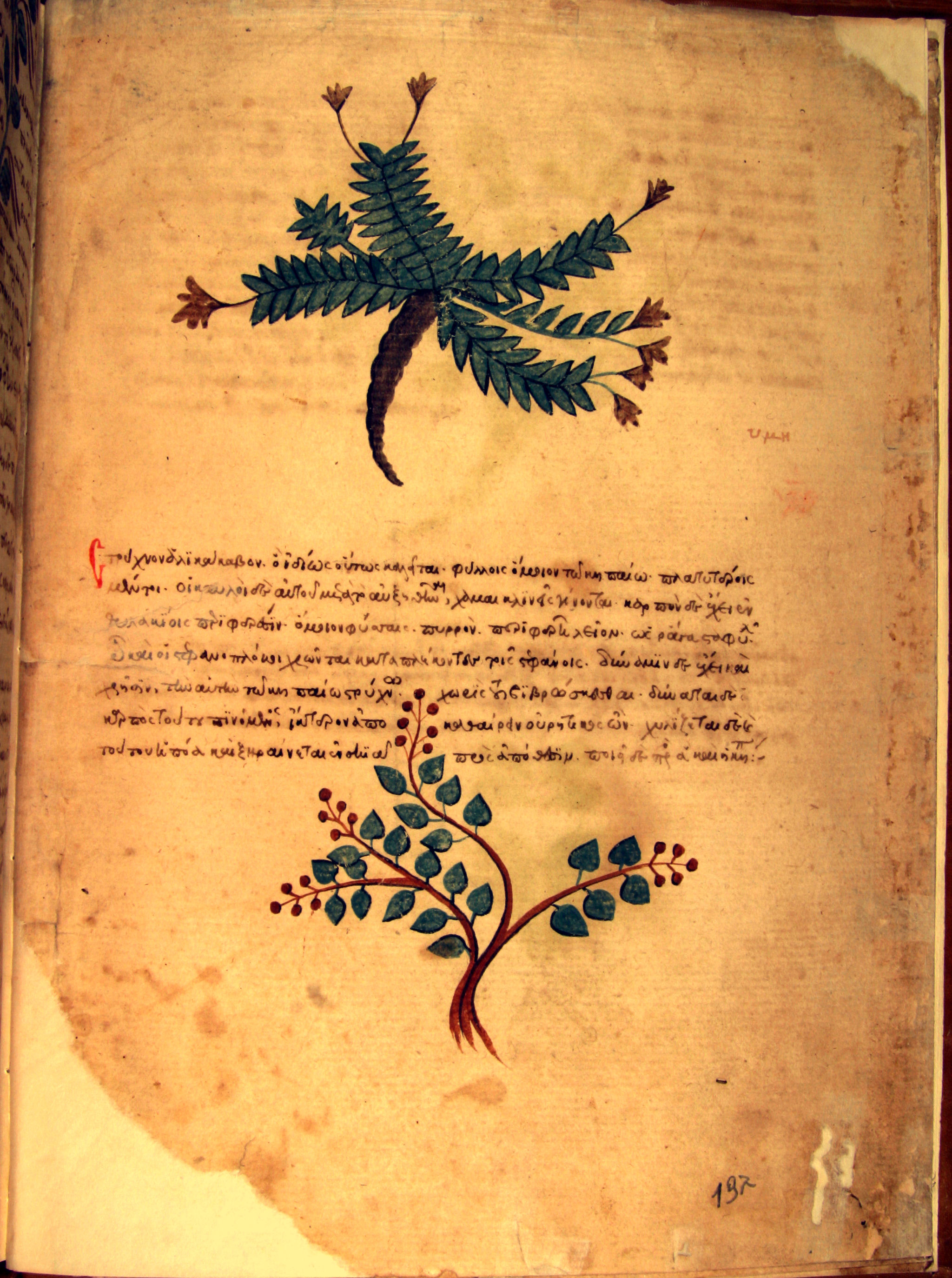

8. Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, f. 169r

(φυσαλλίς-fusallis)

9. Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, f. 197r

(στρύχνον-ἁλικάκκαβον-struchnon alikakkabon)

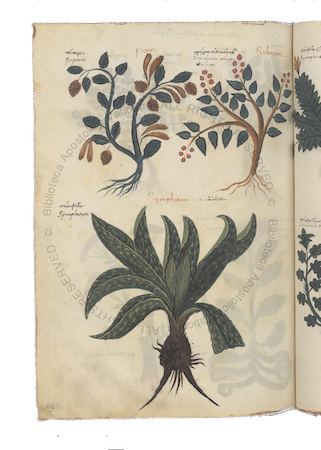

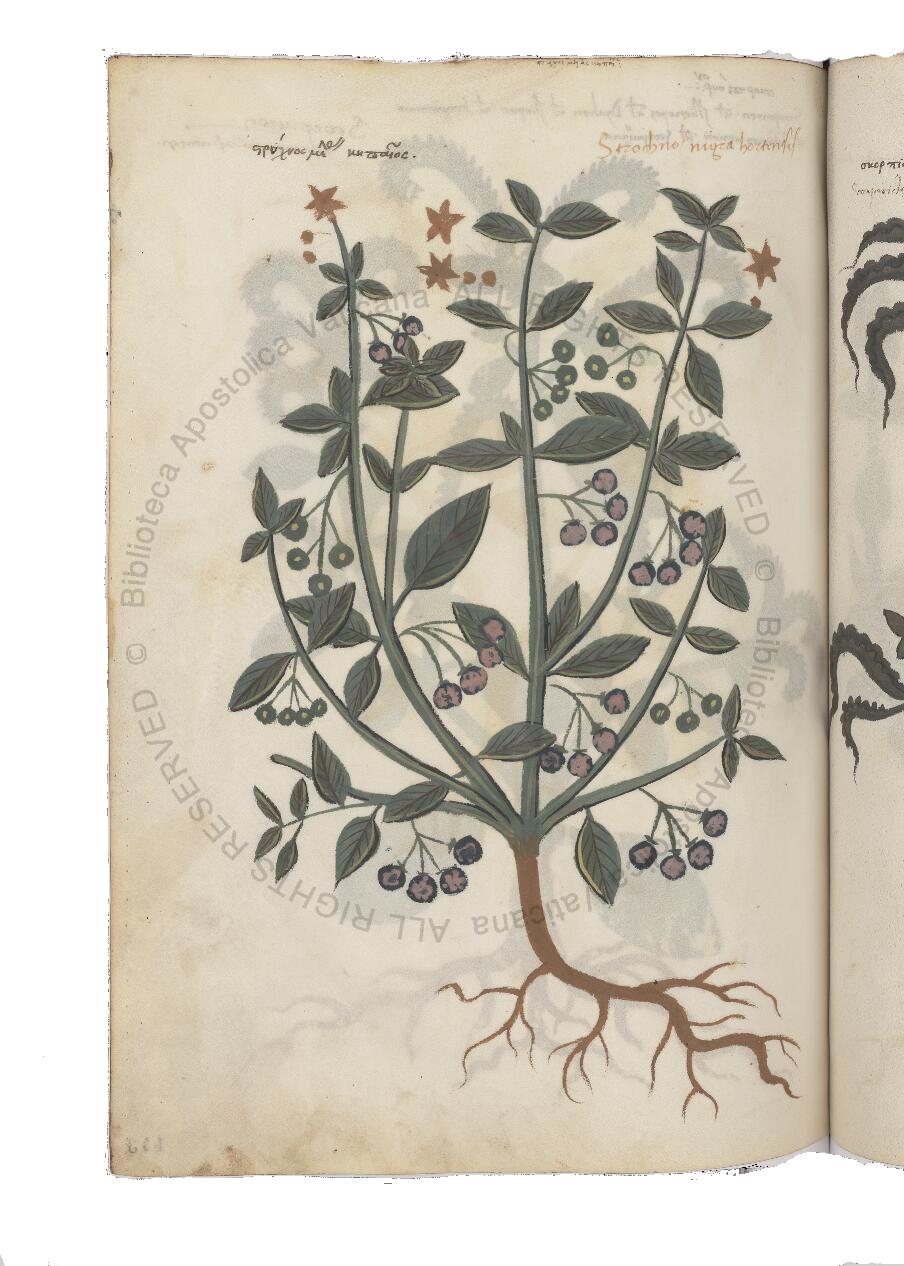

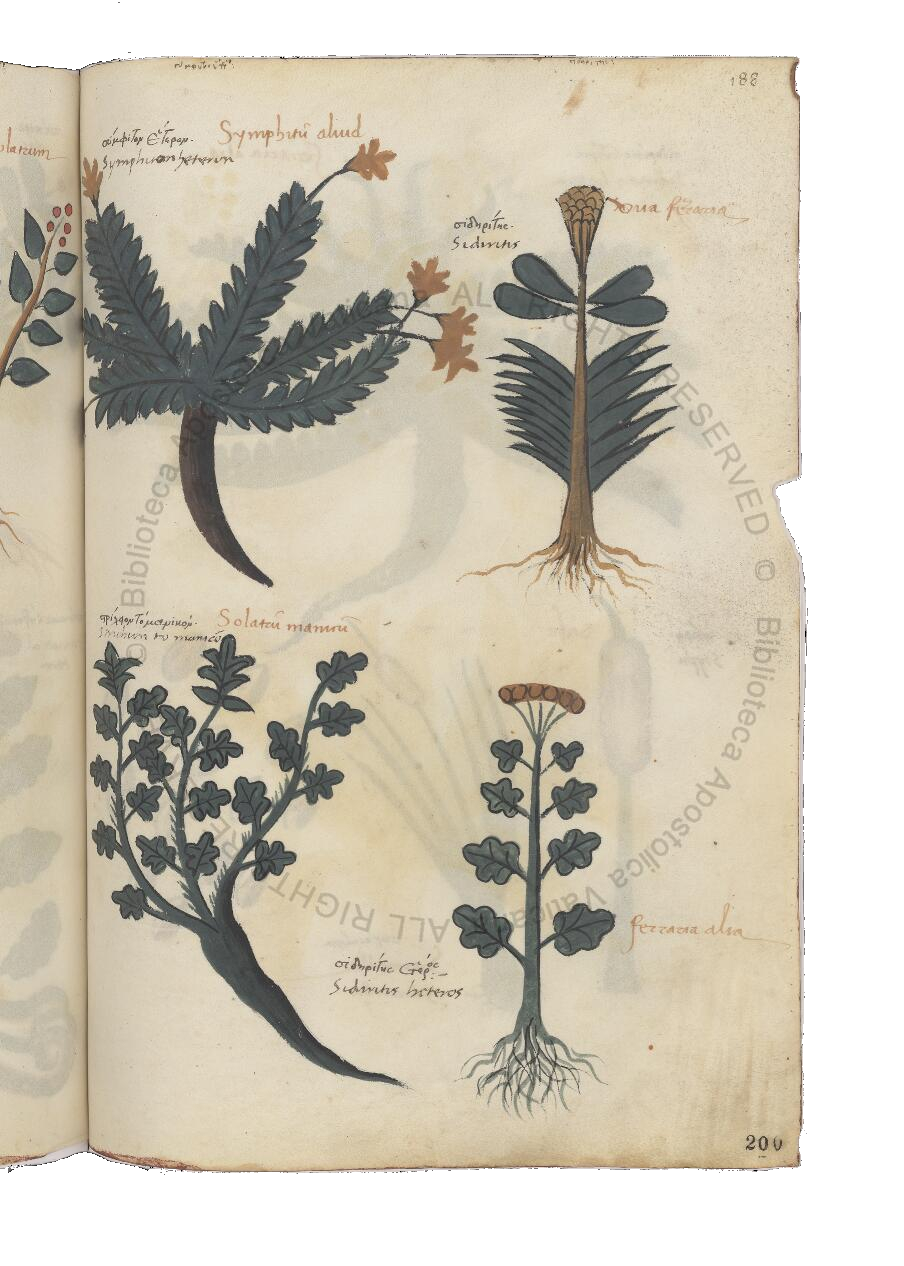

10. Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Chigi F.VII.159, f. 199v

(στρύχνον-ἁλικάκκαβον-struchnon alikakkabon)

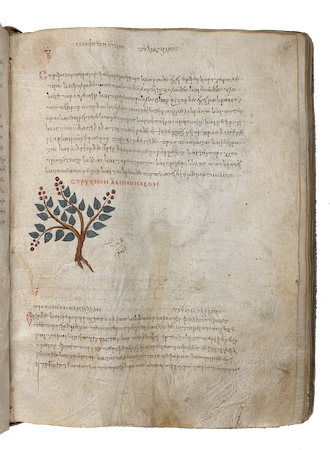

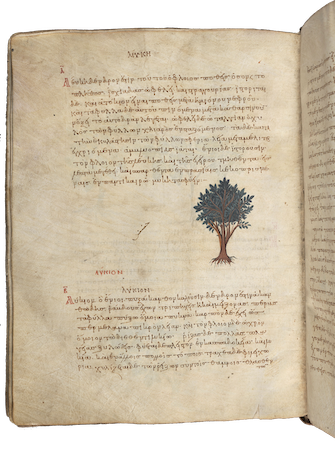

11. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M 652, f. 255v

(λύκιον-lukion)

12. Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Chigi F.VII.159, f. 215v

(λύκιον-lukion)

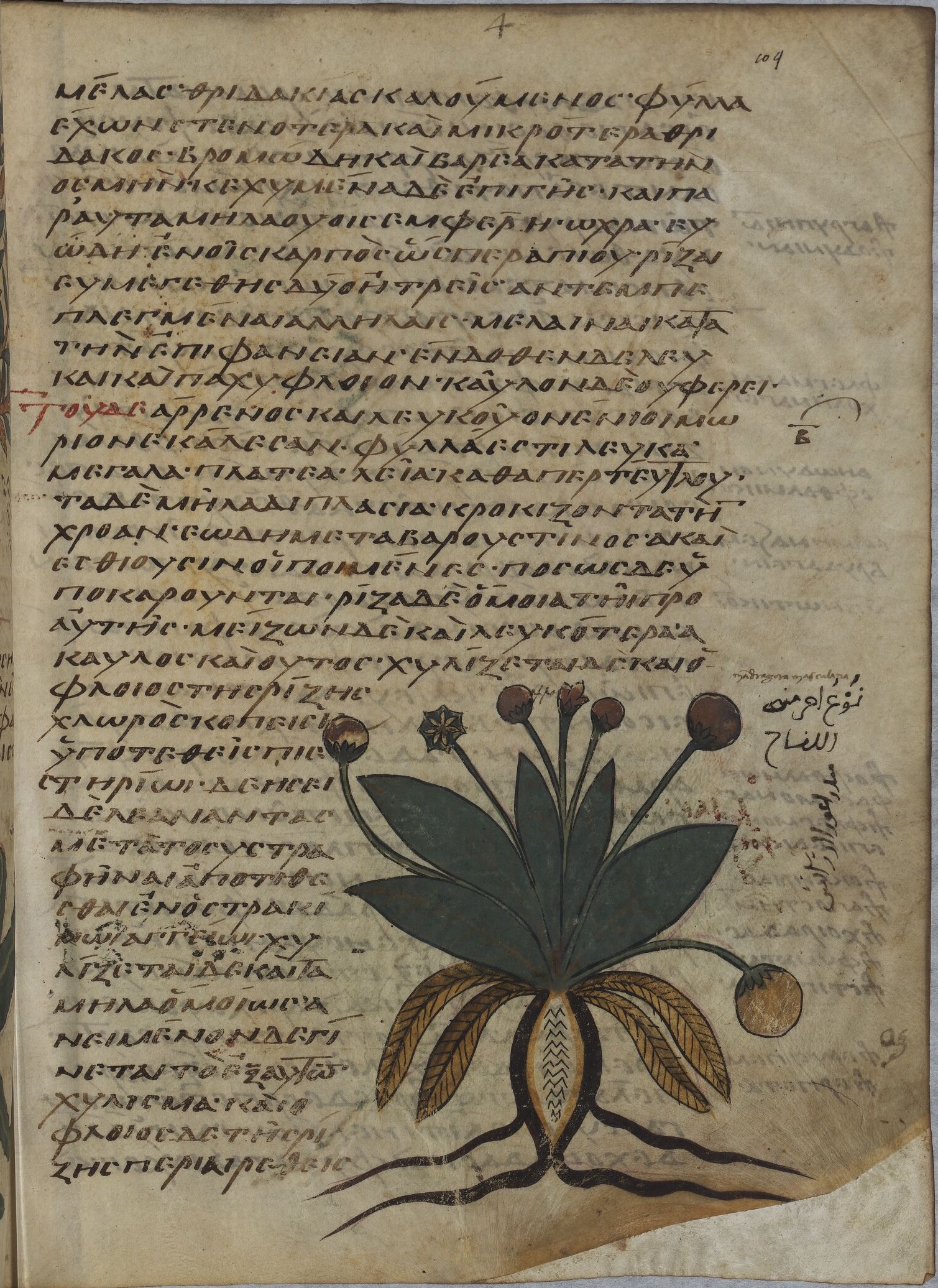

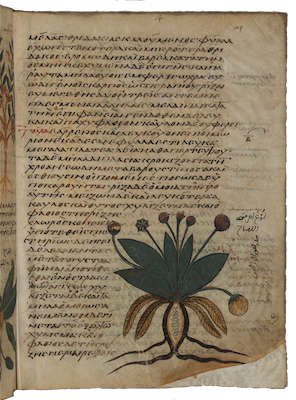

13. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 103v

(μανδραγόρα θῆλυ-mandragora thelu)

14. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M 652, f. 104v

(μανδραγόρα θῆλυ-mandragora thelu)

15. Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, f. 190v

(μανδραγόρα-mandragora)

16. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179 , f. 104r

(μανδραγόρα ἄρρεν-mandragora arren)

17. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M 652, f. 103v

(μανδραγόρα ἄρρεν-mandragora arren)

18. Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, f. 190r

(μανδραγόρα-mandragora)

19. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 101v

(στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion)

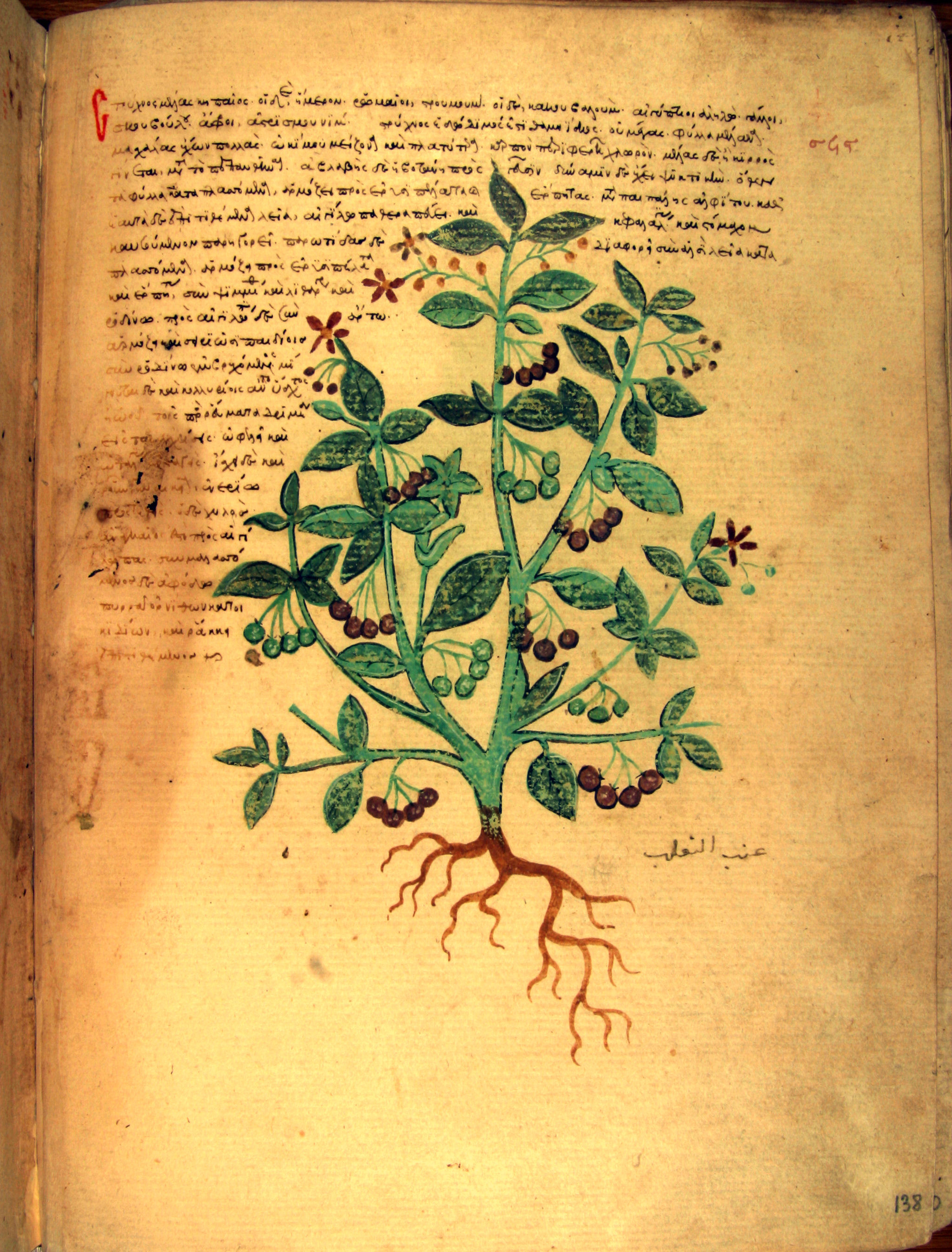

20. Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, f. 138r

(στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion)

21. Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Chigi F.VII.159, f. 143v

(στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion)

22. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 102v

(στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon)

23. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M 652, f. 146v

(στρύχνον τὸ μανικόν-struchnon to manikon)

24. Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, f. 197v

(στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon)

25. Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Chigi F.VII.159, f. 200r

(στρύχνον τὸ μανικόν-struchnon to manikon)

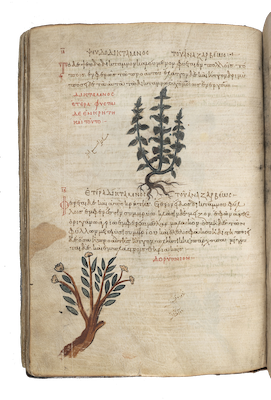

26. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 103r

(στρύχνον τὸ μανικόν-struchnon to manikon)

27. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M 652, ff. 41v

(δορύκνιον-doruknion)

28. Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, f. 185v

(δορύκνιον-doruknion)

29. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, f. 105r

(μώριον-mōrion)

30. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M 652, f. 107r

(μώριον-mōrion)

The very name Solanaceae used by Linnaeus comes from the Latin solanum, which, according to Pliny, Naturalis Histori, 37.132, is the equivalent of the Greek phytonym στρύχνον-struchnon used to identify the taxa identified here as Solanaecae species. Linnaeus did use the Greek term στρύχνον in his taxonomy, but for a botanical genus unrelated to the Solanaceae. This genus is possibly best known through Strychnos nux-vomica L., which is the source of the highly poisonous strychnine. It is native to a region from Bangladesh to Thailand and further introduced to South-central and Southeast China and beyond, and Cuba.

The Solanaceae species recognized in the botanico-medical literature of ancient Greece are the following (alphabetical order of ancient Greek names) with their identification according to contemporary Linnean, binomial taxonomy:

| ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon | Physalis officinarum Moench (= P. alkekengi L.) | |

| δορύκνιον-doruknion | Physalis officinarum Moench (= P. alkekengi L.) and [?] Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (=Physalis somnifera L.) | |

| λύκιον-lukion | Lycium europaeum L. | |

| μανδραγόρας-mandragoras | Mandragora officinarum Bertol. | |

| στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion | Solanum nigrum L. | |

| στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon | Datura stramonium L. and Atropa bella-donna L. | |

| στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon | Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal |

Material for this study is both textual and iconographic (botanical tables in manuscripts of the relevant texts) used independently or in combination.

The texts considered here are chapters and fragments about the following seven Greek phytonyms (in alphabetical order of their Greek name):

- δορύκνιον-doruknion

- λύκιον-lukion

- μανδραγόρας-mandragoras

- στρύχνον ἕτερον -ἁλικάκκαβον- struchnon eteron alikakkabon

- στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion

- στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon

- στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon

The phytonyms have been identified in Dioscorides, De materia medica (1st cent. A.D.), with complements from the following eight treatises by Galen (129-after [?] 216 A.D.) and two Pseudo-Galenic works of later epoch (listed in alphabetical order of standard Latin titles):

- De alimentorum facultatibus

- De compositione medicamentorum per genera

- De compositione medicamentorum secundum locos

- De methodo medendi

- De sanitate tuenda

- De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis et facultatius, abbreviated here as De simplicibus

- De temperamentis

- In Hippocratis De articulis

and the following two pseudo-Galenic treatises:

- De remediis parabilibus

- De succedaneis

All these texts are reproduced in the original Greek language in Appendix I on the basis of their current standard edition. For the purposes of easy reference in the analysis, they are sequentially numbered from [1] to [57], with possible subdivisions for some of them (e.g. [20.1]). A list of the selected passage follows the texts.

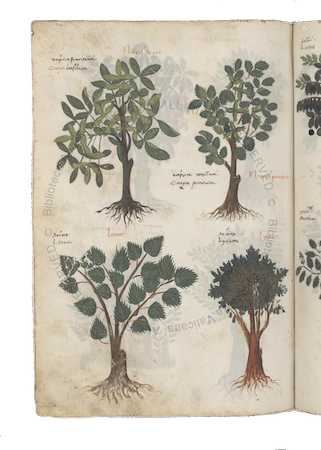

Not all manuscripts contain a representation of all the plants under study here and not all representations provide the same level of botanical information. The manuscripts of interest selected here are the following (in plausible chronological order):

- Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale Emanuele III, Ex Vindobonensis graecus 1, 7th century

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, graecus 2179, 8th century (?)

- New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M 652, 10th century

- Padua, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile, 194, 14th century (2nd quarter)

- Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Chigi F.VII.159, 15th century

Although not all represent the same iconographic tradition, they offer significant convergences, possibly hinting at a common origin.

It is remarkable that no manuscript of Galen, De simplicibus contains plant representations, except one. This exception is the 10th century manuscript Vaticanus graecus 284 that merges De simplicibus and Dioscorides, De materia medica, in a unique and idiosyncratic ways. The small plant representations in the margins adapt the structure of the representations to the oblong format at the margins, sometimes taking advantage of the free spaces at the end of the lines and inserting twigs or leaves between the lines of the text. In fact, these plant representations were not part of the original programme of the manuscript, but were introduced later, apparently during the 14th century. No manuscript of other Greek botanical or pharmaco-therapeutic treatise contains plant representations scientific in nature.

All plant representations are listed in Appendix II, which includes a table of concordance.

For several taxa, Dioscorides provides synonyms (lemmas and synonyms are in bold):

- [1.1] λύκιον, ὃ ἔνιοι πυξάκανθαν καλοῦσι, ...

- [4.1] ἔστι δὲ καὶ ἕτερον στρύχνον, ὃ ἰδίως ἁλικάκκαβον καλοῦσι ...

- [5.1] στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν, οἱ δὲ ἁλικάκκαβον, οἱ δὲ κακκαλίαν καλοῦσι ...

- [6.1] στρύχνον μανικόν, ὃ ἔνιοι πέρσειον, οἱ δὲ περισσόν, οἱ δὲ ἄνυδρον, οἱ δὲ πεντόδρυον, οἱ δὲ ἔνορυ, οἱ δὲ θρύον, οἱ δὲ ὀρθόγυιον ἐκάλεσαν ...

- [7.1] δορύκνιον, ὃ κρατεύας ἁλικάκκαβον ἢ καλλέαν καλεῖ ...

- [8.1] μανδραγόρας · οἱ δὲ ἀντίμιμον, οἱ δὲ βομβόχυλον, οἱ δὲ κιρκαίαν [, οἱ δὲ διρκαίαν] καλοῦσιν

Although these synonyms might not have all appeared in De materia medica from its original form, they are instructive.

The synonym πυξάκανθαν for λύκιον is almost glossed by the short chararacterisation of the plant that follows [1.2]: δένδρον ἐστὶν ἀκανθῶδες. Interestingly, this segment of De materia medica text is exacly reproduced by Galen in De simplicibus [19.1] and [19.2], unless this is an addition made to align Galen’s text on that of De materia medica.

The term ἁλικάκκαβον is used for three different phytonyms: [4.1] ἕτερον στρύχνον, [5.1] στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν, and [7.1] δορύκνιον. Whereas this might be interpreted as the result of a confusion between all three species, it probably indicates that the three plants were identified as taxonomically related.

The higher number of synonyms for [6.1] στρύχνον μανικόν and [8.1] μανδραγόρας probably hints at the place that these plants had in popular tradition because of their potent action on humans.

In the iconographic body, a new phytonym appeared (e.g. the manuscripts Naples f. 148r and Padua f. 169r): φυσαλλίς, which replaced the name of the στρύχνον not better identified than by ἕτερον στρύχνον [4]. This term is not used in De materia medica and must be considered as heterogeneous. As it will be seen below, it probably originates from a botanical characteristic of the plant that unmistakably distinguishes it and is especially visually translated in the iconography.

Galen lists the plants in the alphabetical order of ir most common name, which does not provide any information about botanical taxonomy. He nevertheless used some taxonomical criterion, which resulted here in a simple dichotomy edible/non-edible illustrated by στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion [54.1] vs. ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon [9.1]. The difference between the two species is already present in Dioscorides, without being a taxonomical criterion, however. The chapter of De materia medica on ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon follows indeed that on στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion. It specifies that ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon has “the same indications as the previous one” [= στρύχνον κηπαῖον] except that it is not eaten”. In Galen, the opposition is not just about these two taxa, however. About ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon, Galen specifies that it is “among those species of στρύχνον-struchnon that are not edible”, which is more general. Only the species κηπαῖον- kēpaion is explicitly said to be edible. Its name in both Dioscorides [3.1] and Galen [54.1] clearly indicates that it is a garden/cultivated plant. Galen is more explicit, writing that “it grows in gardens and all know it” [54.1]. But this might be again an addition to Galen’s original text. Returning to the dichotomy edible/non-edible, it was not necessarily translated into alimentary usages with their consequences, as we shall see.

In terms of taxonomy, Dioscorides proceeded differently in De materia medica: he grouped the plants in coherent clusters (the exact nature of which might not be pharmaco-chemical as often stated) and ordered the resulting clusters on a scala naturae from iris to soot. In this system, all the taxa of the Solanaceae family studied here are grouped in book 4 except one: [1] λύκιον, which appears in the part of book 1 devoted to trees. This results from the arborescent nature of the plant, identified in the very first word of the chapter devoted to it: δένδρον ἐστὶν [1.2]. Its representation in the MS New York, f. 255v, and its copy MS Vatican, f. 215v, although generic, visualizes this structure. Though unrelated in botanical taxonomy, λύκιον-lukion nevertheless bears some therapeutic similarity with the other Solanaceae (below). Its position among the tress results from a classification system that combines botanical structures (tree in the present case) and as much as possible pharmacotherapeutic properties, though without exclusivity for the latter.

All the other Solanaceae species identified (recognized?) in De materia medica form a group in book 4 ( chapters 70-75), although they correspond to no less than six different species in modern Linnean taxonomy. Confirming this taxonomical proximity, three species are designated in the way of the Aristotelian taxonomical system of γένος and εἶδος), with a γένος name (στρύχνον) that identifies the genus, and epithets that distinguish a εἶδος; these epithets refer to descriptive factors different in nature: horticultural (κηπαῖον [3]), pharmacotherapeutic (ὑπνωτικόν [5]), or toxicologic (μανικόν [6]).

The coherence of the groups is indirectly confirmed in the substitution list attributed to, but not by Galen. As its pseudo-autobiographical introduction suggests, substitution was invented as an emergency measure in a case of unavailability of a drug. A closer examination contradicts this story and reveals that substitution is a mere pharmacotherapeutic device that expands the range of substances to be possibly applied in a treatment, being understood that substitutes have the same or similar therapeutic properties as the substituted drug. According to De succedaneis, substitutions can be made between genera of Solanaceae genera and species:

| substituted drug | subtituting drug | |

| ἁλικάκκαβον | δορυκνίου ἢ στρύχνου σπέρμα [15.1] | |

| μαδραγόρου | χυλός δορύκνιον [27.2] |

The unity of the group is further reinforced by its position within book 4 of De materia medica. A substantial part of this book is devoted to plants considered toxic as per ancient criteria. The group of the Solanaceae is framed by ψύλλιον-psullion (4.69) and ἀκόνιτον-akoniton (4.76), both of which were credited with a toxic action in the ancient toxicological literature. Whereas ψύλλιον-psullion provokes a sharp loss of bodily temperature followed by narcosis and insensivity, ἀκόνιτον-akoniton provokes an immediate loss of consciousness, and oppression on the chest and the abdomen (gastro-intestinal system) leading to death. Between these two toxic activities—defined in Antiquity by coldness for ψύλλιον-psullion and mind and chest disturbance for ἀκόνιτον-akoniton—the Solanaceae under consideration here present a rather unitary action on the human body. Galen defines it at length and repeatedly in the theoretical books of De simplicibus and returns to it on several occasions throughout his production, in treatises related to materia medica and pharmacotherapeutics, and not only.

Returning to substitutions, they are not always about related taxa as above, but can also be between unrelated taxa, be it for the subtituted or the substituting drug, as in the following cases (alphabetical order of Greek names of substituted plants; names of Solanaceae taxa in bold):

| substituted drug | subtituting drug | |

| ἀλόη Ἰνδική | ... λύκιον ... [20] | |

| δορύκνιον | ὑοσκυάμου ἢ ἐλελισαφάκου σπέρμα [18] | |

| κυνόσβατος | ἁλικακάβου σπέρμα [15.2] | |

| μανδραγόρας | ἐλαίας δάκρυον [27.1] |

Whereas the substituted or substitute plants in all the cases above are not credited with a potent physiological action, in one case, instead, one of the substitutes (ὑοσκυάμου ... σπέρμα) [18] is a powerful drug (a species of the Hyoscyamus genus). This is also the case in the following substitution where a Solanaceae substitutes opium poppy:

| substituted drug | subtituting drug | |

| μήκων | μανδραγόρου χυλός [27.3] |

In a slightly different way, Galen groups some Solanaceae (δορύκνιον and μανδραγόρας) with potent plants that include opium poppy (μήκων-mēkōn) in one case [16]; hemlock (κώνειον-kōneion) and the less active Plantago spp. (ψύλλιον-psullion) in another [23]; opium poppy and henbane (ύοσκύαμος-uoskuamos) in a third [24]; and also, opium poppy and hemlock in a last one [26]:

δορύκνιον, μήκων, μανδραγόρας [16]

μανδραγόρας, κώνειον, ψύλλιον [23]

μήκων, ύοσκύαμος, μαδραγόρας [24]

μήκων, μανδραγόρας, κώνειον [26]

In a similar way, Dioscorides compares the action of στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon to that of μήκων-mēkōn (opium poppy) [5.4].

The connection of ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon, δορύκνιον-doruknion and μανδραγόρας-mandragoras with such plants as κώνειον-kōneion (hemlock), μήκων-mēkōn (opium poppy), and ύοσκύαμος-uoskuamos (henbane) indicates that the three Solanaceae here have an action similar to that of the other three plants, which were identified as toxic. In fact, στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon [6bis.3] and δορύκνιον-doruknion [7.4] are considered lethal in De materia medica, but only if consumed at higher doses. The common point between the Solanaceae and the other lethal agents here is their cooling nature (actually deadly), repeatedly affirmed by Galen (below) and best illustrated by hemlock. This explains why the group of Solanaceae appears among the toxic drugs in De materia medica, even though none of them is explicitly defined as toxic.

Whereas Dioscorides provides a morphological description of the taxa under study here in the chapter devoted to each of them, Galen does not do so, as he is less interested in botany than in pharmacotherapeutics.

In his descriptions, Dioscorides proceeds in a typical, though unsystematic way, with both a general description (structure) and an analytical one (the parts) and, for the latter, from root to top. In the description of the parts, he considers their shape, number and dimension, appearance and consistency/texture, colour with possible differences according to the annual life cycle, organoleptic qualities in some cases, and any other element that might be distinctive.

All descriptive characters presented by Dioscorides for the taxa studied here are tabulated in English in two tables: Table 1 about all the taxa except mandrake, and Table 2 for mandrake only.

Table 1

Botany — All taxa except Mandragoras

| Shape | Root | Stems | Leaves | Flower | Fruit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alikakkabon [4.2] | folding downward when grown |

|

| |||

| Doruknion [7.1] |

| less than 1 cubit |

| white |

| |

| Struchnon kēpaion [3.2] |

| abundant |

|

| ||

| Struchnon manikon [6.2] |

|

| white |

| ||

| Struchnon manikon [6bis.1] |

|

| ||||

| Struchnon upnōtikon [5.2] | bush |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2

Botany — Mandragoras

| Female [8.2/1] | Male [8.2/2] | Mōrion [8bis.1] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | black | white | |

| Leaves |

|

|

|

| Fruit |

|

| |

| Root |

|

|

|

| Stem | none | none |

This tabular presentation, comparative in nature, evidences significant features that the textual presentation, sequential in nature and, consequently, fragmented, does not allow. The most salient characteristic revealed by this tabular presentation is the focus on the fruit, the description of which is present for all taxa, contrary to what happens for the other structural elements of the plants, which are treated in a non-systematic way. Description of the fruits refers in an almost systematic way to the following parameters:

structure

shape

colour, with possible evolution over time

dimensions

numbers when applicable

organoleptic qualities (touch)

comparison with well-known plants, including difference(s)

Comparison is frequently used to distinguish the two species (female and male, in this order) of μανδραγόρας-mandragoras [8], and also μώριον-mōrion [8bis] (Table 2). In other cases, Dioscorides compares parts of the taxa here to those of others, for example the leaves of λύκιον-lukion to those of Boxwood and its fruit to Pepper [1.2]. Also, when describing στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon, he compares its leaves to those of Quince tree [5.2] and, in describing the fruit of στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon, he compares it to grape [6bis.1]. In typically Aristotelian method, in several of the comparisons, he includes both a common element and a difference. If he compares the leaves of στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion to those of Basil, he immediately adds that they are longer and larger [3.2]. He does the same for the leaves of ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon, comparing its leaves to those of the previous plant (στρύχνον ηπαῖον- struchnon kēpaion), mentioning, however, that they are larger [4.2]. Other such cases are those of στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon the leaves of which recall those of Rocket although they are smaller [6.2], and its fruit, which is like the olive, but hairy (below) [6.2]. The leaves of the Olive tree are used to describe those of δορύκνιον-doruknion, wich are smaller, however [7.2].

This focus on the fruit and the lack of systematicity about the other parts of the plants reveal the exact nature of plant descriptions in Dioscorides: they are not aimed at offering a full botanical description but concentrate on the characteristic(s) that allows for correct identification in a functional way. As a consequence, the lexicon of the different parts of these descriptions is differentiated: whereas it is generic and non-specific for all the parts that are not the fruit, with the possible exception of the general shape (tree, bush, low plant), which refers to the Theophrastean quadripartite division of the whole plant world, for the fruit, instead, it is precise and descriptive, with a selected lexicon (especially for the shapes), with a higher number of comparisons that connects specific plants to more familiar and well-known species.

This diagnostic function of the plant description is reflected in the representations that accompany the text in several manuscripts. The clearest—but not unique—case is that of ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon: its fruit is described as a round capsule similar to bladder that contains a yellow/orange fruit, round, light, and like grape, which is represented in a vivid color in the manuscripts, and in a persistent way from the most ancient to the most recent (below). Such focus on meaningful diagnostic characters might have contributed in some cases and manuscripts to give a non-natural appearance to plant representations.

Dioscorides provides some information about the habitat of the taxa. Στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon ὑπνωτικόν grows in rocky places [5.3] while στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon in mountainous and windy ονεσ, as well as in areas planted with Plane trees [6bis.2]. Δορύκνιον-doruknion grows in rocky places close to the sea [7.3], and μώριον-mōrion in shady areas and in the proximity of caves [8bis.1].

Information on distribution is almost absent. Only for λύκιον-lukion does Dioscorides specifies the region from which it comes from: Cappadocia and Lycia—the latter as an etymology—and in numerous other places not otherwise identified [1.3]. A similar distribution in Cappadocia and Lycia is found in Galen [19.5].

Considering the characteristics of each taxon provided in De materia medica and focusing on the fruit as a uniquely distinctive diagnostic device as did Dioscorides (see Tables 1 and 2), while consulting at the same time the representations of the plants in the manuscripts (see the list by plant in Appendix II and their reproduction at the end of this study), identifications at the level of genus and species can be proposed for the ancient phytonyms studied here. Identifications below (reflecting updated taxonomy) include the plant diagnostic characteristic(s) that allows for the identifications with a brief discussion based on modern floras (alphabetical order of Greek names).

|  |

| μανδραγόρας | Mandragora officinarum Bertol .(.) | |

| Both the male and female species correspond to Mandragora officinarum L. = M. autumnalis Bertol., the flowers of which can be whitish or purplish. This colour difference probably justifies the distinction of a female and a male species of the ancient texts. The dark colour of the female species (to be understood as referring to a darker/deeper, not black strictly speaking, and probably referring to individuals with purplish flowers), which apparently contradicts the gendering of colour in the ancient Greek world (dark = male vs. light = female), might refer to a meaning of dark as a negatively connotated colour. The colour of the fruit of each species, instead, reflects the ancient gender distinction, with the greenish fruit of the female species and the saffron-like of the make species. In addition to colour, size and smell oppose the two species: the female species is smaller, has leaves with a fetid and heavy smell, and a fruit with a pleasant smell instead, whereas the male species has long and large leaves without the fetid odour of the female species, and the same pleasant odour of the fruit, but stronger and heavier. The representations in manuscripts accentuate this dichotomy of the two species, particularly the smaller size of the female species (from left to right: MS Paris f. 103v; MS New York f. 104v; MS Padua f. 190v) opposed to that larger and stronger of the male one (MS Paris f. 104r; MS New York f. 103v; MS Padua f. 190r). |

|  |  |

Female mandrake

|  |  |

Male mandrake

| στρύχνον κηπαῖον | Solanum nigrum L. | |

| The general shape of the plant, the shape and dark colour of the leaves, and the round fruit, green or black and yellowish when ripe, well represented in the manuscripts although the colour of the fruit is exclusively dark (from left to right: MS Paris, f. 101v; MS Padua f. 138r; MS Vatican f. 143v), all allow for an identification as Solanum nigrum L. |

|  |  |

| στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν | Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (= Physalis somnifera L.) | |

| Diagnostic elements in Dioscorides’ description of this taxon are contradictory. Whereas the general description (shape, stems, leaves) fits well Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal to which this Greek phytonym is usually identified, neither the color of the flower nor the structure of its fruit correspond. Its flower is white/yellow instead of red as per Dioscorides. Its fruit forms a cluster unlike the solitary berry implicitly mentioned in Dioscorides’ text and represented in a manuscript (MS Paris f. 102v). |

| The part of the plant to be used as identified in the list of its therapeutic indications provides an important key: it is designated as a corymb in both Dioscorides [5.6] and Galen [55]. Although the term is not correct from a strict botanical viewpoint, it may have been applied to describe the cluster of fruits of Withania somnifera. In addition to the shape and color of the fruit, correctly identified as a berry of a saffron-like color by Dioscorides and represented as such in the manuscript, this designation of the fruit supports the identification above. All these elements are distinctive characteristics of this taxon and distinguish it from Solanum nigrum L., for example. |

The case of στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon and δορύκνιον-doruknion, with two identifications each, requires further explanation.

| στρύχνον μανικόν | Datura stramonium L. and Atropa bella-donna L. | |

Strangely enough, the text offers the description of two fruits with very distinctive characteristics defined as follows in Dioscorides’ text [6.2] and [6bis.1]:

These characteristics are incompatible. Interestingly, the second set of characteristics is introduced by the expression “afterwards”, which should notbe referred to a chronological evolution of the fruit through the annual life cycle and maturation process, but rather to the physical organization of the page of a book, meaning that there is one description followed by the other. This “afterwards” most probably indicated that some folios or parts of text had been lost . As a result, the first description of a fruit is immediately followed by another one in a sequence that did not correspond to the usual structure of Dioscorides’ chapters. In this view, the first fruit is unmistakably that of Datura stramonium L. with its typical prickly capsule. The representations in the manuscript are not about this fruit, but about the second above, as a grape. This identification contradicts the native distribution of the Datura genus traditionally considered to be typical of the New World and introduced to the Old World in the Renaissance. However, textual evidence here supports its presence in the ancient Mediterranean World. The second fruit seems to evoke Solanum nigrum L. especially because of its corymb structure compared to that of Ivy fruit, its color, and number. While some manuscripts offer images of an unspecific plant (from left to right, MS New York f. 146v; Padua f. 197v, 1st plant; MS Vatican f. 200r, lower right), another represents a plant with pods containing a certain number of seeds instead of a corymb as described in the text (MS Paris f. 103r). The effects of the plant as described in the text [6bis.3] favor identification of this second fruit as that of Atropa bella-donna L. |

|  |  |

| δορύκνιον | according to Kratevas: Physalis officinarum Moench (= P. alkekengi L.) | |

| and | ||

| [?] Withania * * somnifera * **(L.) Dunal (= Physalis somnifera L.) | ||

| The case of δορύκνιον-doruknion is different. Dioscorides opens the chapter stating that the root-cutter (drug-provider) Kratevas (1st cent. B.C.) calls it ἁλικάκκαβον/καλλέα-alikakkabon/kallea, the former of which recalls a species of struchnon [4]. He then provides the description, which does not correspond to that of ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon. According to this description, δορύκνιον-doruknion is a plant like a young olive tree, with leaves like those of the olive tree, but longer and narrower, rough, a white flower, and a fruit in pods, like chickpea, with 5-6 small round seeds like Bitter vetch, soft on the external side, but hard and of different colours. The representations in manuscripts partially correspond to such a description (on the left, MS New York f. 41v. 2nd plant; on the right, MS Padua f. 185v, 1st plant), with a trunk and branches with leaves similar to those of the olive tree. They correspond in both manuscripts (the Paduan is a copy of the New York one) and are clearly a creation that visualizes some elements of the description in the text. |

|  |

| The general description might favor an identification as Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (= Physalis somnifera L.), the twigs and pods of which are villous (recalling the adjective rough used by Dioscorides about the leaves), the inflated calyx (a pod like that villous of Chickpea), and the seeds. The sleep-inducing property of the plant and its toxic effect at higher dose reinforce this identification. |

The plant μώριον-mōrion is not considered here [8bis]. In the description of μανδραγόρας ἄρρην-mandragoras arrēn (male mandrake), Dioscorides mentions that it is sometimes called μώριον-mōrion, suggesting that this phyonym is just a synonym of μανδραγόρας ἄρρην-mandragoras arrēn. Nevertheless, he treats it in the following chapter as a species of its own. Even though he reports popular sayings, he includes a description [8bis.1]. Whereas its leaves recall those of the male species of mandrake, its root is simple, intead of intertwined, with the distinctive shape of that of mandrake [8.2/1]. No fruit is mentioned. The representations in the manuscripts visualize such characteristics in a rather schematic shape that shows insufficient knowledge of the plant (on the left, MS Paris f. 105r; on the right, MS New York f. 107r).

|  |

According to popular beliefs, consumption of a drachma of the plant has a singular effect: “the man sleeps in the position he had when he ate it, without perceiving anything for three or four hours from the moment he took it”. To this, Dioscorides adds, nevertheless, that the plant is used by surgeons as an anesthetic and that it is believed, in a further popular tradition, to be an antidote to the intoxication by στρύχνον μανικνόν-struchnon manikon [8bis 2-4].

Textual information has been transformed in data (in English) parsed in a table created to account as precisely as possible of the information contained in the texts, express in the most accurate way their content and, at the same time, to make renewed study possible. The table contains the following fields:

- medical conditions with

- body part

- condition

- plant (Solanaceae taxa)

- text with

- reference to the texts in appendix (number from [1] to [57])

- plant (drug)

- part of the plant

- form

- co-ingredients

- pharmaceutical form

- expected results

The field “Medical condition” is divided into two parts. The first lists the body parts are expressed as per the ancient texts, by specific bodily parts, major physiological systems, interpretative physiological systems (the four humors), pathological conditions, or any other categorization explicit or not in the texts. The second part of the field records the medical conditions mentioned in the texts. These conditions are taken at face value. They are symptological and not etiological, even though Galen refers to hypothetical etiological mechanisms to explain the action of the Solanaceae in some cases (below), exactly as he does for other taxa. None of these mechanisms have been taken into consideration here. The field “Plant” that follows, lists the phytonyms of the Solanaceae considerred here according to a transcription of their Greek name into Latin alphabet. This next field (“Text”) refers the text from which information has been collected. In its first sub-field, it contains the numbers from [1] to [57] attributed to the texts collected for this study and reeproduced in Appendix I. Its second sub-field mentions the name of Dioscorides (abbreviated Diosc.) and Galen in order to perceive the possible differences between the two. The fields “Plant” is not a repetition of the field with the same title, but is about the materia medica obtain from the plants. It is divided into two sub-fields: “Part” is about the parts of the plants that were used, and “Form” about the form under which these parts were used medicinally. The field “Co-ingredient” mentions the possible other substances used with the plants in order to pepare medicines, and the next, “Pharmaceutical form” indicates the kind of medicines that were prepared. The field “Expected results” translates the verbs used in the description to express the efficacy of the medicines. These verbs are translated into English as “heals”, “alleviates”, “is indicated” or similar. This field also includes more general information such the mention of the property of a plant.

Pharmacotherapeutics—All taxa

Based on the textual corpus presented in Appendix I, Table 3 contains 207 items and 10 datapoints for each, resulting in a total of 2,070 datapoints, including a certain number of negative value meaning that no information is offered by the text. Of these 197 items, 117 come from Dioscorides, De materia medica (= 56 %), and 90 (= 43 %) from 8 treatises by Galen and 2 Pseudo-Galenic ones. The datapoints with negative value total 255, with 95 of them in uses from Dioscorides’ text (= 37 %) and 160 (= 62 %) from Galenic and Pseudo-Galenic texts.

On the basis of Table 3, a table has been created for each of the 7 plants studied here (Tables 4.1 to 4.8). Two tables have been generated for στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion (Tables 4.5 and 4.6). Galen used indeed the term τρύχνον-truchnon and στρύχνον-struchnon for the species named στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion by Dioscorides [53]. These tables are identified by the name of the taxon they are about (names in the form of the Latin transcription of their Greek names). They consist of the same fields as Table 3.

Alikakkabon

Doruknion

Lukion

Mandragoras

Struchnon kēpaion

Struchnos

Struchnon manikon

Struchnon upnōtikon

As the analysis and numbers that follow show, Dioscorides and Galen did not have the same approach in the pharmacotherapeutic analysis of the drugs under consideration here. This is nowhere clearer than in the comparison of the Tables 5 and 6 about στρύχνον κηπαῖον struchnon kēpaion and στρύχνον-struchnon, respectively. Table 5 contains only uses provided by Galen, whereas Table 6 contains only uses provided by Disocorides.

Dioscorides is systematic, providing information not only as abundant, but also as precise as possible, in a factual and descriptive way without investigating or speculating on the mechanisms of the medicinal uses he reports. Only in two cases does he introduce theoretical reasoning in listing the uses of a taxon. One is about στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion. Dioscorides states its general action (cooling [3.4]) and then presents its applications as resulting from that property in a deductive way [3.5]. The other case is about ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon [4.5], where the reasoning is presented in the opposite way: not as a deduction going from the principle to the use, but as cause going from the use to the principle [4.4]. Galen, as for him, does not indicate the part of the plant to be used in 57 % of the cases and the form in which their parts should be used in 48 % of the cases (below). This should not be interpreted as a lack of accuracy or, even less, of interest. Galen’s focus is elsewhere: it is on identifying an overarching concept of the action of the plants. As the analysis of the therapeutic profile below makes it plain, Galen proceeded by induction from the analysis of the specific applications and then formulating a general concept in abstract terms that subsumes all applications. He proceeds as Dioscorides did for στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion, by formulating a general property and listing then applications as a deduction of that property (ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon [9.4], λύκιον-lukion [19.4], μανδραγόρας-μανδραγορας [22.1]).

Apart from some cases studied below where the materia medica for the medicines is a product prepared from a plant, in all other cases the substance for the preparation of medicine is of plant origin.

Only in one case does Dioscoride mention that one species is of better quality (more potent): λύκιον-lukion [1.9]. He specifies the characteristics to recognize it, both chromatic (external and internal colour of the root) and organoleptic (smell and taste).

When dealing with that same drug, Dioscorides refers to adulterations and explains how they were made [1.9]. Contrary to what he usually does, he does not add here methods for detecting the adulteration. However, since the authentic product is odorless and the adulterations are made by adding substances with a characteristic smell, method of detection is implicit.

Whereas Dioscorides systematically identifies the part of the plants to be used—except in the case of δορύκνιον-doruknion [7]—Galen does not do so in 49 cases (= 62 % of his mentions of Solanaceae) (above).

The parts are the following, with the number of uses and the references to the texts (the number of uses is higher than the number of texts referred to as parts of plants in the same text may have several uses):

Whole plant

16 uses (14 in Dioscorides, 2 in Galen)

[3.6], [4.4], [4.5], [4.6], [6], [7.4], [35], [4.5]

Root

57 uses (50 in Dioscorides, 7 in Galen)

[1.10], [5.7], [6bis.3], [8.6], [8.7], [8.8], [8.11], [8bis.4], [13.1], [17], [24], [55]

Root epidermis (cork in Greek)

7 uses (5 in Dioscorides, 2 in Galen)

[5.4], [5.6], [8.12], [13.2], [25]

Twigs

6 uses (all in Galen)

[12]

Leafage

12 uses (all in Dioscorides)

[4.6]

Leaves

27 uses (all in Dioscorides)

[3.5], [4.4], [8.10]

Fruit

12 uses (7 Dioscorides, 5 Galen)

[4.5], [5.5], [5.6], [8.13], [10], [55], [56], [57]

Seed

3 uses (2 in Dioscorides, 1 in Galen)

[8.14], [55]

Splinter from the bark-like root epidermis

1 use (Galen)

[13.2]

Roots are the most used part, with 57 uses (entire, ground or as a source of juice) and 7 of the epidermis. Total number of 64 represents 32 % of all uses. Leaves (also entire, ground or as a source of juice) come second with 39 uses (leafage and leaves) corresponding to 15 %.

The form in which the plants were used (e.g. fresh vs. dry, entire vs. ground) clearly indicates that plants were mostly used fresh. They were either acquired from a provider or harvested from an orchard adjacent to the houses, possibly also with a part specifically devoted to growing medicinal plants. This possible difference in the sources for procurement might reflect a difference between urban and rural situations.

Dioscorides specifies the form in which parts of the plants must be used for thereapeutic applications. Contrary to his general use, he does not provide such information in 22 cases (= 18 % of his total number of uses of Solanaceae). These cases are either obvious ([4.5], [5.4], [5.5], [5.6], [6bis.3]) or related to a use reported as unsure [7.4]. Galen does not identify any form of the drugs in 60 cases ( 66 % of the uses he mentions).

Fresh

25 uses

leaves: 19 uses [3.5], [4.4], [8.10], [12]

twigs: 6 uses [12]

Fresh and ground

leaves: 8 uses [3.5], [4.4]

Dry

1 use (whole plant, fruit) [4.5]

Ground

root: 5 uses [8.11]

leaves: see above under fresh

fruit: 2 uses [10]

Juice (cold pressing)

total uses: 68

undetermined (whole plant?): 21 uses [3.6], [4.4], [19.3], [38], [39],[41], [42], [43], [44], [49], [50], [51], [52]

whole plant: 12 use [3.6], [4.4]

root: 23 uses [1.10], [5.7]

leafage/leaves: 12 uses [4.6]

Boiled

4 uses (root, root epidermis) [5.6], [8.6], [13.2]

in one case, boiling of the root epidermis is explicit avoided [8.12]

Cleaned

splinter cleaned in vinegar for use as a toothpick [13.2]

Pickled

8 uses (leaves) [8.10]

Only for some of the species studied here does Dioscorides characterize their therapeutic action in general terms with the following:

- astringent (λύκιον-lukion) [1.10]

- cooling, refreshing or, probably better, heat-lowering (στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion [3.4] and ἁλικακκαβον-alikakkabon [4.4])

- sleep-inducing (upnōtikos) (στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon), resulting in almost a tautology [5.4].

Galen delves much more into the general typification of the action of the Solanaceae species with different approaches that might sometimes lead to divergent statements.

For λύκιον-lukion, he does not only identify its action in general terms as desiccative, but he explains it in function of his system of material analysis of its substance which, in this specific case, is finely-particled, diaphoretic and hot, and at the same time, earthy, cold and styptic [19.4].

For στρύχνον-struchnon approached as a genus without identification of a species, he repeatedly specifies that it is cooling [30] and [31] as Dioscoride about στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion [3.4], and, in one case, he recommends a list of plants that includes στρύχνον-struchnon and the more general class of the cooling substances [39]. This cooling property is combined with astringency in two passages [33] and [54.2], and this combination is said to be obtained also from opium poppy and mandrake in addition to στρύχνον-struchnon [36] and δορύκνιον-doruknion [16]. In another case, this cooling activity goes with moistening [34] and in still another with desiccation [53].

Στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon, specifically, is highly cooling [55] but less than opium poppy. Its seed is diuretic [55] as is also the leaf of ἁλικακκαβον-alikakkabon, which has the same general property as στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion [9.4].

The action of mandragora, indistinctive of the species female or male, is defined in a similar way as cooling [21], with the same property and some moisture in both the whole plant [26] and its fruit [22.1] in a combination that is also present in opium poppy and hemlock [26]. In one passage, the plant is characterized as cooling and desiccative [22.2].

This general characterization of the action of the plants accounts for their use in the treatment of some medical conditions. In the case of στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion, Dioscorides makes an explicit connection between its cooling property and its use in the treatment of skin pathologies, cephalgia and burning stomach [3.4]. A similar relationship from property to use is stated by Galen about the diuretic action of ἁλικακκαβον-alikakkabon, which justifies the use of the plant in many compound medicines without any further explanation [9.4].

Toxicity is stated about some plants, mostly because of excessive dose (below). In one case, however, it is attributed to the whole substance of the plant, without any influence of dosage; even a minimal dose provoked total damage, as Galen puts it [57].

In some cases, the intensity of the property of a plant is measured in imprecise terms, on a degree-scale or in comparative terms. Although this is the backbone of Galen’s analysis of materia medica—particularly the objective measuring on a four-degree scale with interemediary degrees—it already appears in Dioscorides though in a less systematic and less formal way. Dioscorides considers στρύχνον μανικον-struchnon manikon as very diuretic [5.5] and moderatley sleep-inducing compared to opium poppy [5.4]. As per his own system, Galen is more precise on this. If he proceeds by comparison in some case [16], in another he combines both comparison and exact degree on his four-degree scale [55], and in still two others he precisely measures the property on the scale, with an exact degree [53] [54].

According to the number of uses for each plant, μανδραγόρας, with 45 uses (= 22.8 %), closely followed by στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion and its equivalent στρύχνος-struchnos in Galen with 44 uses (= 22.3 % of the total number or uses). They are followed by, λύκιον-lukion with 29 uses (14 %), and ἁλικάκκαβον with 28 uses (= 14 %). The much lower numbers of uses of all other three species results from different factors: στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon (7 uses), though being indicated to treat odontalgy [5.6], amblyopia [5.7], dysuria [5.5] [55] and dropsy [5.6], as well as general pain [5.6], was also sleep-inducing [5.4] [55] and potentially toxic (mental disturbance) if taken in doses higher than therapeutic [55]. The case of δορύκνιον-doruknion is similar (6 uses): whereas Galen uses it to treat major conditions as well as articulartions and gout [17], Dioscorides reports, instead, that it seems to induce sleep and even lead to death if taken abundantly [7.4]. Assuming that the δορυκνίδιον-doruknidion mentioned by Galen (6 uses) is the same as δορύκιον-doruknion, the same lethal property is reported when the plant is taken in excessive dose [16].The στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon (5 uses) is credited with only one therapeutic properties [8bis.4], and mostly with mental disturbance by Galen [55] [56] [57], and by loss of consciousness and death by Dioscorides [6bis.3]. The difference between the two groups reveals a clear knowledge of the risks presented by some species (below).

Considering the body parts for the treatment of which Solanaceae were used, Table 3 highlights three major fields of use listed below by number of uses and fraction of the total number of uses (percentage): skin (40 uses = 20 % of the total number of uses), eyes and sight (31 uses = 15 %), head (18 uses = 9 %), with a total of 41 % of all uses.

However, a cross-reading of the table beyond bodily parts brings to light actions with equally significant numbers and percentages of uses: anti-inflammatory action from abcesses to gangrenous wounds, with 26 uses (= 14 %), and catharsis from evacuation of bile and phlegm to gout, with 17 uses (= 9.5 %).

A comparison of the uses of each plant indicates some common effects as table 5 clearly shows, with 39 uses for skin affections (= 19 %), 31 for the eyes (= 15 %) and 17 for the head (= 8 %). All these are for external use in a significant way, and total 87 (= 44 %).

Table 5

Comparisons of taxa

Taxa | Bodily parts/actions | |||||||

Skin | Eyes | Head | Digestive system | Psyche | Gynecology | Urinary tract | Lethal | |

Alikakkabon | 11 | 6 | 4 | 3 | - | - | - | - |

Doruknion | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

Lukion | 9 | 6 | - | 9 | - | 2 | - | - |

Mandragoras | 12 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 5 | - | 1 |

Struchnon kepaion | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | |

Struchnos | 3 | 7 | 9 | 2 | - | - | 1 | - |

Struchnon manikon | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | 1 |

Struchnon upnotikon | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 3 | - |

Total | 39 | 31 | 17 | 14 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

As indicated above, three species were known for their toxic action: στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon, στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon, and δορύκνιον-doruknion to which μανδραγόρας/ μώριον-mandragoras/mōrion should be added.

For the first three, doses higher than therapeutic are responsible for the iatrogenic effects. For στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon, a dose in excess of 12 corymbs provokes great excitement, probably agitation and mentally unsound behavior in a way that is reversible, however if properly treated [5.6]. The species στρύχνον μανικόν-struchnon manikon, also, is credited with psychoactive properties that were differentiated and increased according to the doses: whereas one drachm is described as provoking llustions that are not unpleasant, two drachms disturb the mind for up to three days and four can even lead to death [6bis.3]. The case of δορύκνιον-doruknion, which Dioscorides reports with caution, is similar as it can be sleep-inducing and lethal in higher dosage, without an exact definition of the sub-lethal/lethal dosage [7.4]. The latter two are not reported as reversible.

Μανδραγόρας-mandragoras and μώριον-mōrion (which might refer to the same plant) are a case of its own. Eating or smelling its fruit or consuming its juice induces sleep and provoke aphonia when taken in excess [8.13]. Whereas two obols of the juice from the root eliminates phlegm and bile, a higher quantity leads to death [8.7]. Shepherds are said to consume the fruit of male μανδραγόρας-mandragoras, which provokes a certain stupefaction [8.2/2].

For μώριον-mōrion, which might be a species of mandrake if not mandrake itself, Dioscorides reports an extraordinary action that he does not endorse, however, saying that it is popular narrative and belief: it instantly provokes a loss of consciousness, leaving those who drink or eat it either in a maza or as a foodstuff in the exact position they had when they took it, without feeling anything for three or four hours from the moment they absorbed it [8bis.2].

The sleep-inducing inducing of μανδραγόρας/ μώριον-mandragoras/mōrion benefited surgery (cutting and burning) thanks to the anesthesia (in the etymological meaning of the word, lack of sensivity as per Dioscorides’ explicit wording [8.6]) [8.6], [8.12] [8bis.3].

Pharmaceutical activity about the Solanaceae consisted in preparing two major types of products: drugs for the preparation of medicines and the medicines themselves.

1. Preparation of drugs for medicine-making

Dioscorides describes the preparation of some materia medica that are stored in appropriate containers for later use.

For one of the Solanaceae—μανδραγόρας-mandragoras—Dioscorides describes a process to collect in the field what he identifies as a liquid. It consisted of digging around the root and collecting the liquid flowing from the root. We must assume that an incision in the root was necessary for this liquid to exude. As Dioscorides adds, roots did not produce such liquid in all places, something that could be learned by experience. In any case, this liquid was less active than the juice obtained from the root [8.15]. Considering the whole set of popular beliefs that accompanied mandrake, this might be an addition, so more so because it appears at the end of the chapter on μανδραγόρας-mandragoras. The detail about experience coming at the very end of the phrase contributes to doubting the authenticity of this whole segment.

Other parts of the μανδραγόρας-mandragoras required specific treatment. The epidermis of the root was cut when still green and pressed. The juice was exposed to the sun to be reduced and then conserved in a clay recipitent [8.3]. The epidermis could also be hung on a thread and kept for further use [8.8], exactly as was the case for the root of iris, which was cut in slices that were hang on thread and dried in a shady, ventilaed place. The root itself can also be boiled in wine, reduced to a third, filtered and kept for a future use [8.6]. The leaves can be pickled and preserved [8.10] and the fruit can be processed as the root epidermis, that is, pressed to obtain a juice that is then exposed to the sun and reduced to be further preserved [8.4].

For λύκιον-lukion [1.5], [1.7], [1.8]), the drug is not the plant itself, but a derivative obtained from either its root and leafage or its fruit. Root and leafage are cut and kept moist for a sufficient number of days, then boiled and reduced until the liquid reached the consistency of honey [1.5]. Aduteration takes place during this boiling process, by pouring into it amurca, wormwood juice, or ox-bile [1.6]. It is detected by its odour. The foam floating on the boiling solution is collected and used as a drug in itself [1.7]. A similar process is used for the juice of the fruit, which is not boiled, but reduced by exposition to the sun [1.8].

Another drug can be prepared and stored for later use: the juice obtained from στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion [4.5] and from ἁλικακκαβον-alikakkabon [4.5] that is condensated in the shade and kept for storage.

2. Ingredients used in the preparation of medicines

Besides the Solanceae that constitute the main ingredient of medicines—be it in the form of a fresh plant or a prepared drugs made with one of them and preserved for later use—, medicines include other substances, with both excipients and substances that can be identified as co-ingredients, although the difference might not be always as clearcut as this binary opposition suggests. Such other substances are mentioned in 75 cases (ca. 40 % of the whole uses).

In external use, excipients can be bread [3.6], [4.4]; goose fat [10], [48], honey [5.7], [50] or oil [8.11]. In internal use they can be Barley groat [3.6], [4.4], [8.10], [8.11], [35], water [1.10] [8.11], and wine [5.4], [5.6], [6bis3], [8.6], [55].

The list of these ingredients—be they excipients or co-ingredients—follows:

Barley groat [3.6], [4.4], [8.10], [8.11], [35]

Bread [3.6], [4.4]

Crocus [44]

Egg [3.6], [4.4]

Galbanum [42]

Goose fat [48], [10] Galen

Henbane [25]

Honey [50], [5.7]

Illekebra moss [42]

Libanos [42]

Lithargyrum [3.6], [4.4], [44]

Melikraton [5.6], [8.7]

Muron [48], [10] Galen

Native sulphur [8.14], [44]

Oil [8.11]

Psimithium [3.6], [4.4], [44]

Rose oil [3.6], [4.4], [38]

Salt [3.5], [4.4]

Vinegar [8.11], [13.2], [14], [39]

Vinegar [47]

Kedria [47]

Propolis [47]

Vinegar [13.1]

Oak gall [13.1]

Water [1.10], [3.6], [4.4], [8.11]

Wine [5.4], [5.6], [6bis.3], [8.6], [8.12], [55]

In De materia medica, Dioscorides does not systematically describe preparations of medicines, which is understandable as the work is about materia medica and not pharmacopoiesis. If he sometimes mentions medicines, he mostly lists the main ingredients and the possible excipient or co-ingredients without any other information and without systematic indication of dosage of the ingredients. In some cases, however, he provides a more detailed description as for an anesthesiant wine for surgery [8.12], which is made of the epidermis of the root of μανδραγρόρας-mandragoras (3 man) infused in a proportional quantity of wine, without boiling as explicitly specified.

As can be expected, Galen is specific in his pharmaceutical treatises, the tey organized by types of medicines or by the bodily parts for which medicines were prescribed (De compositione medicamentorum per genera and De compositione medicamentorum secundum locos, respectively). In the former, he lists the ingredients with the quantity of each [44], [45] to form trochiscs to be stored for use when necessary. In the latter, he proceeds in the same way in one case, without specifying, however whether this is a medicine for immediate consumption or for storage [25]. In the other case, he reproduces a formula of Asclepiades, which he modifies. The formula includes instructions for the preparation. After the list of the ingredients with their respective quantities, it prescribes to boil the juice of two ingredients and a gum; when the gum has melted, another gum should be added. Whereas the original formula prescribes mastic, Galen substitutes it with galbanum probably in the same quantity as mastic [42].

The Pseudo-Galenic treatise De remediis parabilibus procceds in a similar way with ingredients and quantities for two medicines prepared for immediate administration [50], [51], and in a slightly imprecise way for two others: one which is simple [49] and another made of three ingredients, two of must be in a quantity that is not exactly defined, but must be equal for both [48].

The pharmaceutical form and road of administration is often, but not always indicated. It is explicitly present in over 100 cases (= 56 % of all uses). In many cases, it can be deduced from the imperatif form of the verb meaning “taking”, which refers here to an oral administration in the form of a potion.

Pharmaceutical forms are varied. Not only do they distinguish external and internal administration, but they also identify special forms of administration. For external use, they can be applications, an aspersion, bandages, cataplasms, frictions, ointments, and tampons. For internal use, they can be colliria, gargling, infusions, instillations, potions, clysters, and suppositories. Some forms are not identified as pharmaceutical forms stricly speaking but as classes of medicines (e.g. antalgics), which may be assumed to have been of a certain pharmaceutical form. Each form was determined in function of the condition to be treated.

Their list follows with the total number of each when higher than two, and in all cases the references to the texts (numbers between brackets in bold).

Antalgics [5.6]

Applying

16 uses

[4.4], [3.5], 1.10], [4.5], [8.14], [12], [8.10], [12], [45], [49]

Aspersion [3.6], [4.4]

Bandages (made of wool) [49]

Breathing [8.13]

Cataplasm

13 uses

[11], [30.2], [30.3], [4], [3.6], [8.10], [4.4], [3.5]

Collirium [3.6], [4.4]

Compound drug [42]

Eating [8.13]

Friction

8 uses

[8.10], [8.11]

Gargling [47], [13.1]

Infusion [13.2]

Instillation [41], [3.6]

Liquid medicine (undetermined)

15 uses

[19.3], [19.4]

Ointment

8 uses

[1.10], [48], [5.7], [38], [48]

Pessary or potion 2 uses [8.7]

Potion

24 uses

[51], [4.5], [55], [56], [8.14], [1.10], [50], [5.6], [8.6], [8.7], [6bis.3], [5.4], [1.10]

Clyster [1.10]

Sponges [39]

Suppository [8.8], [10]

Tampon (possibly applied with wool)

3 uses

[3.6], [4.4], [49]

Trochisc for both external and internal administration

5 uses

[5.6], [14], [25], [44], [45]

5. Place and material for the preparation of drugs and medicines

The place for the preparation of drugs and medicine is not explicitly stated. It can be deduced to have consisted of at least three places: a closed one, with a source of heat; a covered, shady and ventilated one; and an open one, exposed to the sun.

The material to be used to prepare both drugs and medicines is not identified except in two cases: a press [8.3] and a ceramic container for a drug prepared for later [8.3]. On the other hand, the description of a preparation requires use of a strainer [8.6]. The indications provided in the preface of De materia medica —though possibly inauthentic—and logical deductions from the uses made of the plants allow to draw up the following list of instruments to be used whether the plant material was used fresh or not: a press to obtain juice of roots, leafage and fruits, a grater/shreeder to grind roots and fruits, and all the small utensils that could usually be found in a kitchen for the preparation of food with operations like cutting and boiling, from pots of all capacity and size according to the needs to colanders and strainers, as well as small utensils like knives, laddles, skimmers, spoons and others.

Dosage of the medicines to be administred is often absent, except for the lethal threshold of plants credited with toxic properties. Nevertheless, exact quantities are indicated in seven prescriptions:

- στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon administered in a dose of 1 drachm induces sleep [5.4];

- juice from the root of μανδραγόρας-mandragoras without any co-ingredient applied on the cervix in a quantity of half an obol treats amenorrhea and provokes abortion [8.8];

- the same quantity introduced into the anus in the form of a suppository induces sleep [8.8];

- 3 cyaths of anesthesiant wine made of the root of μανδραγόρας-mandragoras should be administered to patients of surgical interventions [8.12];

- a quarter of a choinix of δορύκινον-doruknion should be applied externally to patients suffering of gout, articulations pain, and major conditions [17];

- trochiscs of 1 obol have to be administered internally to patiens suffering of hemoptysis, internal pus, and fluxes [25].

Lethal doses are as follows:

- whereas 12 corymbs of στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν-struchnon upnōtikon treat hydropic patients, a higher quantity provokes mental disturbance [5.6], [55];

- 2 obols of juice from the root of μανδραγόρας-mandragoras taken orally eliminate phlegm and bile orally, and a higher dose is lethal [8.7];

- στρύχνον μανικόν acts differently according to dosage [6bis.3]:

- 1 drachm provokes not-unpleasant illustions;

- 2 drachms generate a state of agitation thant can last up to three days;

- 3 drachms are lethal.

In the case of δορύκνιον-doruknion, the lethal dose is not exactly quantified. According to Dioscorides, the plant seems to induce sleep and, if taken more abundantly, to provoke death [7.4]. Galen offers the same information, without mentioning it as did Dioscorides, but as a fact [16].

The instant sleep-inducing if not lethargic action of μώριον-morion reported above is said to result from a dose as loow as 1 drachm [8bis.2].

The texts include some information about the result to be expected from the medicines for 96 uses (= 54 % of the total numbere of uses). This information is not explicitly stated as such but expressed through 20 different verbs ranging from “treating” to “being indicated”. These verbs vary in function of the medical conditions the plants are used for: dissolves for the treatment of abcesses, cleans for wounds and eliminates for excessive liquids in the body, for example. The term property is used here when the action of the plant is mentioned in abstract without necessarily referring to a medical condition.

These verbs are subjective and may not exactly indicate the degree of efficacy of any use. However, they do not only result for a century-long experience of the plants used medicinally, but also they were used in a persistent and consitent way through the subsequent centuries, a fact that validates them and gives them some objective value, all the more because the texts here have repeatedly been worked on, revised, and commented on, sometimes with substantial textual transformations, both at their macro- and microscopic level (the general structure of the texts and its exact wording).

These verbs (in English translation) are the following with the number of occurrences of each (when higher than 1) and the references to the texts (numbers between brackets from [1] to [57]):

Active on

10 uses

[8.11], [4.5], [4], [3.6], [4.4]

Alleviates [5.7]

Cleans [8.14]

Cures

4 uses

[1.10], [1.11]

Dissolves

11 uses

[8.11], [8.10]

Efficacious

4 uses

[1.10]

Eliminates [1.10]

Evacuates

2 uses

[8.7]

Heals

7 uses

[40], [1.10], [4.4], [3.5]

Helps

5 uses

[4.4], [3.5], [5.6]

Is indicated

12 uses

[9.4], [4.4], [3.6], [4], [8.10], [1.10]

Is useful

2 uses

[4.4], [3.6]

Makes

2 uses

[41]

Property

18 uses

[57], [7.4], [8.13], [5.5], [55], [8.6], [8.12], [8.13], [56], [8.7], [6bis.3], [5.4]

Provokes

2 uses

[8.8]

Reduces

5 uses

[4.4], [3.5], [8.11], [8.10]

Seems to provoke [7.4]

Smothes [8.7]

Stops

5 uses

[8.11], [1.10], [8.14], [4.4], [3.6]

Treats [1.10]

Some non-medical uses of the Solanceae are attested in the textual body examinated here. They are the following:

- alimentary

apart from στρύχνον κηπαῖον-struchnon kēpaion, which was domesticated as its very name indicates and was used alimentary, probably as a leafy vegetable [3.1], [54.1], the fruits of the male species of μανδραγόρας-mandragoras are reported to have been consumed by shepherds, although they provoke a certain stupefaction [8.2/2].

- cosmetic

Λύκιον-lukion was used to make hair blond [1.11].

- decorative

ἁλικάκκαβον-alikakkabon was used in intertwining crowns [4.3] [9.3].

- arts and crafts

According to Dioscorides, ivory boiled with the root of μανδραγόρας-mandragoras for six hours became malleable and could be shaped in any desired form [8.9].

- magics

Dioscorides reports the popular use of δορύκνιον-doruknion in love charms [7.5].

Although written traces of the use of taxa from the Solanaceae family in ancient Greek medicine do not antedate Hippocratic medicine (5th cent. BCE), the substantial body of literature from the Hippocratics onwards doubtlessly attest to precise knowledge and use. The potent effects of some taxa have contributed to creating an aura of mystery and magic around them, mostly attested in non-scientific literature. Nevertheless, these potent effects are referenced in the botanico-medical literature examined here, sometimes with caution as these effects are reported as popular beliefs not necessarily endorsed by the authors whose works have been studied here.

The present preliminary study has focused on Dioscorides, De materia medica, and selected relevant passages from the many treatises by Galen, particularly his major analysis and compendium of materia medica, De simplicibus, and his two major pharmaceutical works on the composition of medicines by affected bodily organs or functions and by pharmaceutical type. Research has identified a more substantial body of material, however, from the Hippocratics to the Early-Byzantine encyclopedists from Oribasius (3rd cent. CE) to the last Alexandrian Paul of Aegina (7th cent. CE).

In this textual body, taxa now identified as members of genera in the Solanaceae family were recognized. They are not explicitly identified as forming a unitary group, even though most of them were grouped in the taxonomy of Dioscorides, De materia medica. Their respective actions indicate both perception of similarity and differentiation.

Whereas Dioscorides in De materia medica provides descriptions of the plants, Galen does not, either in his major work on materia medica (De simplicibus) or in his many other relevant treatises. This is understandable bearing in mind the different focus of these works.

Dioscorides describes the plants in a systematic way from root to top, with a particular focus on the fruit as the comparative analysis through tabulation of textual data has shown. Distinction of the genera and species was made by means of a precise description of the major characteristics of the fruit, using a specific botanical lexicon.

These major characteristics are translated into graphic components in the botanical tables that accompany the text in some manuscripts. Although not all such manuscripts render these characters with the same degree of botanical precision, they somewhat maintain these characters through the centuries.

Combination of textual descriptions and their graphic rendering in botanical tables allows for identification of most of the taxa discussed here according to the binomial Linnean taxonomy. Some taxa cannot be exactly identified, however, for different reasons. Some plants of non-mediterranean origin were unknown contrary to the drugs derived from them. Others were known on the basis of popular beliefs. And still others were identified by names attributed to more than one genus or species.

A remarkable case is the identification of a species from a genus that is traditionally considered as native to the New World: Datura. Philological analysis makes it clear that the chapter in which the plant appears suffered of some loss of text resulting in the fusion of two chapters and the assimilation of two different taxa. Characterization of the two plants brought together in this unitary chapter is clear enough to guarantee identification of the two plants. The fruit of one of them clearly presents the characteristics of the Datura genus. Textual evidence here is strong and provides a further element to the current revision of the sharp divide traditionally made in botanical literature about the distribution of plants between Old and New World.

As for the uses of these taxa, knowledge of their potentially strong psycho-activity is clear, with exact dosage, ensuing gradual differentiation of the effects, and lethality. Knowledge did not necessarily translate into avoidance. Low intensity effects are noted as enjoyable and alimentary consumption with ensuing effect is recorded as a practice of shepherds, possibly as food while in the field. High, but nevertheless sub-lethal consumption was treated appropriately.

Therapeutic uses were principally external, with a prevalence for the treatment of skin and eye affections. Some internal uses are listed, however, including alimentary consumption of the leaves of a taxon. The uses recorded in the texts under analysis here—totaling around 200—form a substantial and differentiated body of data that was continuously and persistently transmitted through the centuries in a way that suggests efficacy.

From a methodological perspective, this preliminary study aimed to bring texts to light and to make them available to non-specialists through textual comprehensiveness, philological accuracy and scientific appropriateness. In addition to laying down the basis for an expanded study of the Solanaceae based on the whole available textual corpus and provided with all the traditional scientific apparatus, it seeks to open the way for a renewed approach to the ancient Greek medico-therapeutic literature and for possible re-examination of its therapeutic arsenal through cross-disciplinary research.

[1] λύκιον Dioscorides, De materia medica, 1.100

Ed. Wellmann 1906-1914: 1.91-92

[1.1.] λύκιον, ὃ ἔνιοι πυξάκανθαν καλοῦσι,

[1.2] δένδρον ἐστὶν ἀκανθῶδες, ῥάβδους ἔχον τριπήχεις ἢ καὶ μείζονας, περὶ ἃς τὰ φύλλα πύξῳ ὅμοια, πυκνά. καρπὸν δὲ ἔχει ὡς πέπερι, μέλανα, πυκνόν, πικρὸν λίαν, καὶ τὸν φλοιὸν δὲ ὠχρόν, ὅμοιον τῷ διεθέντι λυκίῳ, ῥίζας δὲ πολλάς, πλατείας, ξυλώδεις.

[1.3] φύεται δὲ πλεῖστον ἐν καππαδοκίᾳ καὶ λυκίᾳ, καὶ ἐν ἄλλοις δὲ τόποις πολλοῖς ·

[1.4] τραχέα δὲ φιλεῖ χωρία.

[1.5] χυλίζεται δὲ τῶν ῥιζῶν σὺν τοῖς θάμνοις θλασθέντων καὶ βραχέντων ἐφ’ ἱκανὰς ἡμέρας, εἶθ’ ἑψομένων, καὶ τῶν μὲν ξύλων ῥιπτομένων, τοῦ δὲ ὑγροῦ πάλιν ἑψομένου μέχρι μελιτώδους συστάσεως.

[1.6] δολοῦται δὲ ἀμόργης ἅμα τῇ ἑψήσει [vol. 1, p. 92] μειγνυμένης ἢ ἀψινθίου χυλίσματος ἢ βοείας χολῆς.

[1.7] καὶ τὸ μὲν ἐπινηχόμενον ἀφρῶδες ἐν τῇ ἑψήσει ἀφελὼν ἀπόθου εἰς τὰ ὀφθαλμικά, τῷ δὲ λοιπῷ εἰς τὰ ἄλλα χρῶ.

[1.8] γίνεται δὲ καὶ ἐκ τοῦ καρποῦ ὁμοίως χύλισμα ἐκπιεζομένου καὶ ἡλιαζομένου.

[1.9] ἔστι δὲ κάλλιστον τὸ καιόμενον λύκιον καὶ κατὰ τὴν σβέσιν τὸν ἀφρὸν ἐνερευθῆ ἔχον, ἔξωθεν μέλαν, διαιρεθὲν δὲ κιρρόν, ἄβρωμον, στῦφον μετὰ πικρίας, χρώματι κροκῶδες, οἷόν ἐστι τὸ ἰνδικόν, διαφέρον τοῦ λοιποῦ καὶ δυναμικώτερον.

[1.10] δύναμιν δὲ ἔχει στυπτικὴν καὶ τὰ ἐπισκοτοῦντα ταῖς κόραις καθαίρει, ψωριάσεις τε τὰς ἐπὶ τῶν βλεφάρων καὶ κνησμοὺς καὶ τὰ παλαιὰ ῥεύματα θεραπεύει. ποιεῖ καὶ πρὸς ὦτα πυορροοῦντα, παρίσθμια, οὖλά τε εἱλκωμένα καὶ διερρωγότα χείλη, ῥαγάδας ἐν δακτυλίῳ, παρατρίμματα περιχριόμενον · ἁρμόζει καὶ κοιλιακοῖς καὶ δυσεντερικοῖς πινόμενον καὶ ἐγκλυζόμενον. δίδοται δὲ καὶ αἱμοπτυικοῖς καὶ βήττουσι σὺν ὕδατι, καὶ τοῖς ὑπὸ λυσσῶντος κυνὸς δηχθεῖσιν ἐν καταποτίῳ ἢ σὺν ὕδατι ποτόν. ξανθίζει δὲ καὶ τρίχας, παρωνυχίας τε καὶ ἕρπητας καὶ σηπεδόνας ἰᾶται · ἵστησι δὲ καὶ ῥοῦν γυναικεῖον προστιθέμενον.

[2] λύκιον ἰνδικὸν Dioscorides, De materia medica, 1.100

Ed. Wellmann 1906-1914: 1.92

[2.1] λέγεται δὲ τὸ ἰνδικὸν λύκιον γίνεσθαι ἐκ θάμνου, τῆς λεγομένης λογχίτιδος.

[2.2] ἔστι δὲ εἶδος ἀκάνθης, ῥάβδους ἔχον ὀρθάς, τριπήχεις ἢ καὶ μείζους, πολλὰς ἀπὸ τοῦ πυθμένος, παχυτέρας βάτου, φλοιὸς ῥαγεὶς ἐνερευθής, τὰ δὲ φύλλα ὅμοια ἐλαίας,

[2.3] ἧς ἡ πόα ἐν ὄξει ἑψηθεῖσα καὶ ποτιζομένη ἱστορεῖται φλεγμονὰς σπληνὸς καὶ ἴκτερον θεραπεύειν καὶ καθάρσεις γυναικῶν ἄγειν · καὶ ὠμὴ δὲ λεία ποθεῖσα τὰ αὐτὰ ποιεῖν παραδίδοται, τοῦ δὲ σπέρματος μύστρα δύο ποθέντα ὑδατῶδες καθαίρειν καὶ θανασίμοις βοηθεῖν.

[3] στρύχνον κηπαῖον Dioscorides, De materia medica, 4. 70

Ed. Wellmann 1906-1914: 2.228-229

[3.1] στρύχνον κηπαῖον · ἐδώδιμόν ἐστι.

[3.2] θαμνίσκος οὐ μέγας, μασχάλας ἔχων πολλάς, φύλλα μέλανα, ὠκίμου μείζονα [vol. 2, p. 229] καὶ πλατύτερα, καρπὸς περιφερής, χλωρὸς ἢ μέλας · ἔγκιρρος δὲ γίνεται μετὰ δὲ πεπανθῆναι ·

[3.3] ἀβλαβὴς δὲ ἡ βοτάνη πρὸς γεῦσιν.

[3.4] δύναμιν δὲ ἔχει ψυκτικήν,

[3.5] ὅθεν τὰ φύλλα καταπλασσόμενα ἁρμόζει πρὸς ἐρυσιπέλατα καὶ ἕρπητας μετὰ πάλης ἀλφίτου, καθ’ ἑαυτὰ δὲ ἐπιτιθέμενα λεῖα αἰγίλωπας θεραπεύει καὶ κεφαλαλγίας καὶ στομάχῳ καυσουμένῳ βοηθεῖ, παρωτίδας τε διαφορεῖ σὺν ἁλσὶ λεῖα καταπλασσόμενα.

[3.6] καὶ ὁ χυλὸς δὲ αὐτοῦ ποιεῖ πρὸς ἐρυσιπέλατα καὶ ἕρπητας σὺν ψιμυθίῳ καὶ λιθαργύρῳ καὶ ῥοδίνῳ, πρὸς αἰγιλώπια δὲ σὺν ἄρτῳ · ἁρμόζει καὶ σειριῶσι παιδίοις σὺν ῥοδίνῳ ἐμβρεχόμενος. μείγνυται δὲ καὶ κολλυρίοις ἀντὶ ὕδατος ἢ ᾠοῦ τοῖς πρὸς ῥεύματα δριμέα εἰς τὰς ἐγχρίσεις, ὠφελεῖ καὶ ὠταλγίας ἐνσταγείς · ἴσχει δὲ καὶ ῥοῦν γυναικεῖον ἐν ἐρίῳ προστεθείς.

[4] στρύχνον ἕτερον/ἁλικάκκαβον Dioscorides, De materia medica, 4. 71

Ed. Wellmann 1906-1914: 2.229-230

[4.1] ἔστι δὲ καὶ ἕτερον στρύχνον, ὃ ἰδίως ἁλικάκκαβον καλοῦσι,

[4.2] φύλλοις ὅμοιον τῷ προειρημένῳ, πλατύτερον μέντοι · [vol. 2, p. 230 ] οἱ καυλοὶ δὲ αὐτοῦ μετὰ τὸ αὐξηθῆναι χαμαικλινεῖς γίνονται. καρπὸν δ’ ἔχει ἐν θυλακίοις περιφερέσιν, ὁμοίοις φύσαις, πυρρόν, περιφερῆ, λεῖον, ὡς ῥᾶγα σταφυλῆς,

[4.3] ᾧ καὶ οἱ στεφανοπλόκοι χρῶνται καταπλέκοντες τοῖς στεφάνοις.

[4.4] δύναμιν δὲ ἔχει καὶ χρῆσιν τὴν αὐτὴν τῷ προειρημένῳ κηπευτῷ στρύχνῳ χωρὶς τοῦ βιβρώσκεσθαι.

[4.5] δύναται δὲ ὁ καρπὸς τούτου πινόμενος ἴκτερον ἀποκαθαίρειν οὐρητικὸς ὤν ·

[4.6] καὶ χυλίζεται δὲ ἀμφοτέρων ἡ πόα καὶ ξηραίνεται ἐν σκιᾷ εἰς ἀπόθεσιν · ποιεῖ δὲ πρὸς τὰ αὐτά.

[5] στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν Dioscorides, De materia medica, 4. 72

Ed. Wellmann 1906-1914: 2.230-231

[5.1] στρύχνον ὑπνωτικόν, οἱ δὲ ἁλικάκκαβον, οἱ δὲ κακκαλίαν καλοῦσι ·

[5.2] θάμνος ἐστὶ κλάδους ἔχων πολλούς, πυκνούς, στελεχώδεις, δυσθραύστους, φύλλων πλήρεις λιπαρῶν, ἐμφερῶν μηλέᾳ κυδωνίᾳ, ἄνθος ἐρυθρόν, εὐμέγεθες, καρπὸν ἐν λοβοῖς [vol. 2, p. 231] κροκίζοντα, ῥίζαν φλοιὸν ἔχουσαν ὑπέρυθρον, εὐμέγεθη ·

[5.3] φύεται ἐν πετρώδεσι τόποις.

[5.4] ταύτης ὁ φλοιὸς τῆς ῥίζης ἐν οἴνῳ ποθεὶς δραχμῆς μιᾶς ὁλκὴ ὑπνωτικὴν ἔχει δύναμιν τοῦ ὀποῦ τῆς μήκωνος ἐπιεικεστέραν,

[5.5] ὁ δὲ καρπὸς οὐρητικός ἐστιν ἄγαν ·

[5.6] δίδονται δὲ ὑδρωπικοῖς κόρυμβοι ὡς δώδεκα, πλείονες δὲ ποθέντες ἔκστασιν ἐργάζονται · βοηθοῦνται δὲ μελικράτῳ πολλῷ πινομένῳ. μείγνυται καὶ ἀνωδύνοις ὁ φλοιὸς αὐτῆς καὶ τροχίσκοις, ἐναφεψηθεὶς δὲ οἴνῳ καὶ διακρατούμενος ὀδονταλγίας ἀρήγει.

[5.7] ὁ δὲ χυλὸς τῆς ῥίζης ἀμβλυωπίας μετὰ μέλιτος ἐγχρισθεὶς παραιτεῖται.

[6] στρύχνον μανικόν Dioscorides, De materia medica, 4. 73

Ed. Wellmann 1906-1914: 2.231-232

[6.1] στρύχνον μανικόν, ὃ ἔνιοι πέρσειον, οἱ δὲ [232] περισσόν, οἱ δὲ ἄνυδρον, οἱ δὲ πεντόδρυον, οἱ δὲ ἔνορυ, οἱ δὲ θρύον, οἱ δὲ ὀρθόγυιον ἐκάλεσαν ·